This blog post is provided by Ryan Logan and tells the #StoryBehindthePaper for the paper “Patrolling the border: billfish exploit the hypoxic boundary created by the world’s largest oxygen minimum zone”, which was recently published in Journal of Animal Ecology. Blue marlin and sailfish are top predators in the pelagic environment, but little is known about their hunting behavior. Ryan Logan, the lead author of the study, recently finished his PhD at Nova Southeastern University’s Guy Harvey Research Institute on billfish biology and ecology in southeast Panama, and is now working as a post-doctoral fellow in southern California researching the juvenile white shark population. Here, he tells us about one of his studies on blue marlin and sailfish behaviour and how they take advantage of the world’s largest naturally occurring oxygen minimum zone.

How, when, and where animals hunt are fundamental components of the biology and ecology of predators across the globe. In terrestrial environments, this knowledge can generally be obtained through long-term observation of your species of interest. However, in the marine environment, particularly the pelagic ocean, direct observation of predators in a natural setting is not often possible for periods longer than a few minutes.

Because of this difficulty, ecologists track marine predators with satellite transmitting tags and then relate the animal’s movements to that of its environment with satellite imagery of ocean surface conditions. This approach has provided significant insights into long term horizontal movement patterns of several predator species, and revealed that they will concentrate their movements (believed to be foraging related) in areas with strong gradients of some variable (e.g., temperature, salinity, productivity, etc.) termed fronts However, from these same tags, we also know that pelagic predators spend a large proportion of their time moving vertically in the water column, so satellite imagery of surface conditions are unable to tell us the whole story of their movements and behavior.

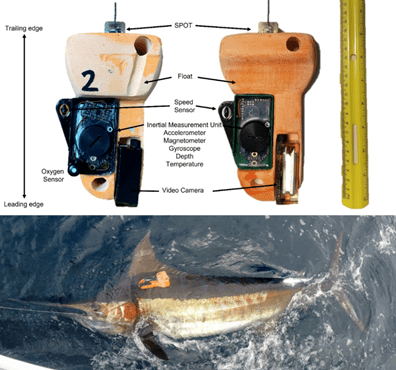

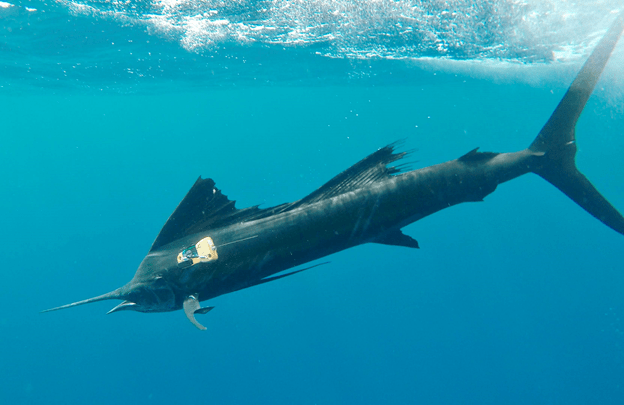

In a recent paper published in the Journal of Animal Ecology, we used a novel combination of very high-resolution motion sensing acceleration tags with speed sensors, dissolved oxygen probes, and video cameras to determine how blue marlin and sailfish might use the vertical fronts of the eastern tropical Pacific (ETP) to hunt. The ETP is home to the world’s largest naturally occurring oxygen minimum zone (OMZ), the upper boundary of which can be as shallow as 20 – 30 m in some places. This creates a distinct vertical boundary (or front) in the water column where the oxygen saturation, temperature, and density changes drastically over a very short distance. Because marlin, sailfish, and their teleost prey are high oxygen-demand species, the upper boundary of the OMZ compresses all of these species to the upper portion of the water column, a phenomenon known as hypoxia-based habitat compression.

Marlin and sailfish prey also tend to be diel vertical migrators, moving into surface waters at night to feed, and deep, darker waters during the day to reduce their own risk of predation. However, due to the OMZ of this region, the vertically migrating billfish prey become concentrated at the upper boundary of the OMZ during daylight hours. Based on our findings, we believe that it is this prey behavior that the billfish predators are taking advantage of.

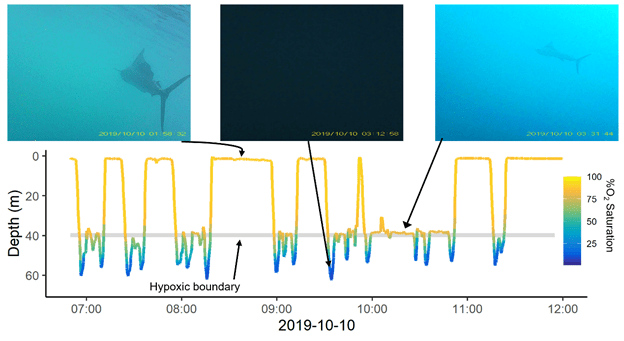

Using a dive shape analysis, we discovered that both blue marlin and sailfish often displayed a characteristic W-shaped dive, where they would descend to the hypoxic boundary, and one or more times during the bottom phase of the dive, would go roughly 10 – 15 m below this hypoxic boundary for short periods of time. Now why would an animal repeatedly dive into cold, dark, low oxygen water if these conditions are unfavorable to their survival? We think we have an answer. They aren’t unfavorable to their survival, in fact, just the opposite.

Based on several lines of evidence, we propose that marlin and sailfish use these vertical fronts to increase foraging success. These predators dive below the vertical fronts 1) because their prey are concentrated just above, and 2) to ambush those prey fish from below. Ambush predation is known to be a very successful foraging tactic across the animal kingdom, yet in the structureless pelagic environment, there is nowhere to hide (for both predator and prey) other than in deep, dark water. We believe that by diving below the hypoxic boundary for brief periods, marlin and sailfish get below their prey and search for silhouettes against the downwelling light, and when prey is encountered, ambush from below. This hypothesis is supported by marlin and sailfish large body sizes (ability to retain body heat for short periods), large eyes (good vision in dark water), brain and eye heaters (high temporal resolution in cold water), and eye morphology (high visual acuity in front and above their head). In a separate study published earlier this year, we documented a predation event from one of our tagged sailfish, in which this W-shaped diving and ambush from below behavior was described in detail, providing further support to the hypothesis we have proposed in the current study.

These findings have larger implications than just this study system. The collective influence of climate change, global deoxygenation and shoaling oxygen minimum zones will reduce suitable vertical habitat available throughout the world’s oceans for many marine species, and will have impacts across ecosystems through direct and indirect pathways. In our study, we provided evidence that the apex predators of the ETP are using the vertical fronts created by the hypoxic boundary layer to their advantage to increase foraging opportunities. Thus, we suggest that predators in other regions currently unaffected by hypoxic boundary layers may be able to behaviorally adapt to spreading oxygen minimum zones and may also be able to take advantage of the creation of shallow hypoxic boundary layers. However, with the predators being mostly restricted to surface waters by the OMZ, it also increases their catchability to surface based fisheries. Because these apex predators play important roles in structuring and regulating ecosystems, understanding how they respond to and use low oxygen environments and the habitat fronts they create is important so real-time management strategies are best equipped to respond to changing open-ocean conditions.

Read the full paper

Logan, R. K., Vaudo, J. J., Wetherbee, B. M., & Shivji, M. S. (2023). Patrolling the border: Billfish exploit the hypoxic boundary created by the world’s largest oxygen minimum zone. Journal of Animal Ecology, 00, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13940

One thought on “Billfish use an oxygen minimum zone boundary to hunt”