This blog post is provided by Gabriel Moulatlet, Wesley Dáttilo and Fabricio Villalobos and tells the #StoryBehindthePaper for the paper “Species-level drivers of avian centrality within seed-dispersal networks across different levels of organization“, which was recently published in Journal of Animal Ecology. In their study, they investigate the factors that influence birds relationships with plants for seed dispersal, in a network context, at both local and global scales. El blog está disponible para leer en Espagnol aquí.

We all have seen birds eating and carrying fruits, or even expelling the seeds, of different plant species (Fig. 1). More often than not, interactions between birds and plants are beneficial for both groups of organisms, with the former receiving food, and the latter the dispersal of their seeds (potential offspring). This type of beneficial interaction that goes both ways is known as mutualistic. In fact, birds are responsible for dispersing the seeds of around 90% of tropical plants! Such relationships between birds and plants can be so important and specific that they determine the existence of either or both species (e.g., if the bird species disappears then the plant may eventually also disappear).

Networks as a tool to study species interactions

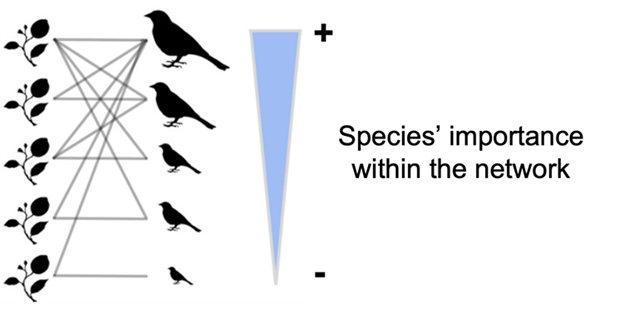

As an ecological phenomenon, seed-dispersal involves several different species of plants and birds across different locations, with some bird species doing a better job than others in maintaining this mutualistic interaction. As with other types of interactions, mutualistic (e.g., pollination) or antagonistic (e.g., parasitism), seed-dispersal interactions have been satisfactorily studied using a network approach in which species are represented by nodes and their interactions as links between such nodes (Fig. 2). Using this approach, it is possible to determine the interactive role of each species within the interaction networks they participate in, also known as their centrality. For example, a bird species can be more or less important (i.e., central) in a network depending on how it is connected to other species of both plants and birds through multiple direct and indirect pathways.

But what makes a species more (or less) central within interaction networks? (e.g., in Fig. 2, the importance of birds in the network is related to body size). Answering this question can help identify what determines the functionality of species within ecosystems and their structure. Knowing which species are more important for ecosystem structure, and which traits allow them to be so, can help mitigate the effects of anthropogenic disturbance on ecosystems by identifying and protecting such species, thus halting the loss of ecological functions. Achieving this goal requires information on several (the most possible!) interaction networks covering different regions, environments, species, and overall variable settings to uncover general patterns and thus general principles and answers.

A macroecological perspective on interaction networks and, believe it or not, friendship and collaboration

As recently explained by Tom Bishop in his post for Animal Ecology in Focus, macroecology is all about searching for “general principles”. In fact, the study of interaction networks has greatly advanced by applying a macroecological approach since at least a decade ago. In our recent study in the Journal of Animal Ecology, we applied such a macroecological approach to find out what determines the importance (centrality) of bird species in seed-dispersal networks with plants. Most studies aiming to identify species’ centrality and their traits have focused on their role within local interaction networks and, when considering a broad spatial scale, on a small set of such local networks (e.g., here and here).

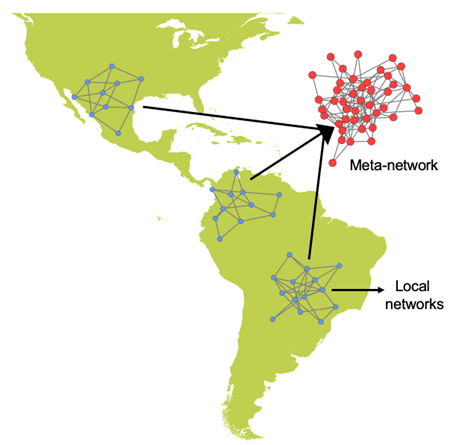

In our study, we compiled and curated a dataset of 308 local avian seed-dispersal networks encompassing five continents and 11 biogeographic regions to identify the drivers of species’ centrality within local networks as well as within the global meta-network, which describes the interactions across all local networks (Fig. 3).

We found that bird species traits (e.g. beak width, body mass, climatic niche, diversification rate, range size, wing length) have different effects on their centrality depending on the network level, thus being scale dependent. The most important driver of bird species’ centrality at the global meta-network level was their geographic range size, with more central species having larger range sizes. Birds with larger range sizes tend to interact with a higher number of plant species, thus they maintain the structure of the seed-dispersal meta-network by connecting several species and different parts of the meta-network together. At the local network level, body mass was the only trait driving bird centrality, suggesting that local factors related to resource availability are more important at this local level of network organization than those related to broad spatio-temporal factors such as range size or evolutionary properties. All in all, we showed that the drivers of species’ centrality in seed-dispersal networks depend on the level of network organization, implying that predicting species functional roles in this mutualistic interaction (and perhaps others) needs a combined (local and global) approach.

Ok but, what does this has to do with friendship and collaboration? Well, it turns out that we (Gabriel Moulatlet, Wesley Dáttilo and Fabricio Villalobos) all come from different research traditions (plant ecology, network ecology, and macroecology, respectively), but the will to find “general principles” in ecology brought us together to design a research project where we could all participate. Indeed, by “averaging over” or even ignoring “details” (a global pandemic, remote meetings, etc.), but paying attention to general trends (e.g., love for Mexico and Brazil, music, and good conversations) allowed us to get funded and develop a successful project to study the macroecology of interactions. Previous steps on this direction from our team have already been published in the Journal of Animal Ecology and we intend to continue doing so.

Team

Our team is based at Institute of Ecology (INECOL) in Mexico, located at the transition zone between the Neotropics and the Nearctic biogeographical regions, along the elevation gradient of the Cofre de Perote mountain that inspired Alexander von Humboldt’s vision of biodiversity gradients.

Read the paper

Read the full paper here: Moulatlet, G. M., Dáttilo, W., & Villalobos, F. (2023). Species-level drivers of avian centrality within seed-dispersal networks across different levels of organisation. Journal of Animal Ecology, 00, 1– 12. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13986

2 thoughts on “What makes a bird important for plants’ seed dispersal?”