This blog post is provided by Johnathan Reyes de Merkle and tells the #StoryBehindthePaper for the paper “An integrated population model reveals source-sink dynamics for competitively subordinate African wild dogs linked to anthropogenic prey depletion”, which was recently published in Journal of Animal Ecology. In their study, they investigated the effects of anthropogenic prey depletion on the coexistence and persistence of the African wild dog, a subordinate predator, within the African large carnivore guild. Johnathan Reyes de Merkle, one of the joint-first authors of the study, is currently working on his PhD at Montana State University in Bozeman, Montana (United States of America).

The Anthropocene era is characterized by the pervasive effects of humans on the environment. Human-caused changes in habitat and resources have the potential to shift fundamental ecological relationships. We investigated the effects of anthropogenic prey depletion on the coexistence and persistence of a subordinate predator within the African large carnivore guild. The endangered African wild dog is a subordinate competitor that has co-existed with dominant competitors for millions of years by avoiding them spatially, hunting at different times, and preying on different herbivores. Lions are a dominant competitor in the African large carnivore guild that place strong limitations on African wild dogs both by killing them and by displacing them from areas with abundant prey. Lion density is strongly correlated with prey density, and because African wild dog density is usually low where lion density is high, African wild dog density is usually low where prey density is high. However, humans are now causing dramatic and widespread decreases in large herbivores across sub-Saharan Africa, and this must eventually limit African wild dogs, even if they simultaneously benefit from decreased lion density. In the extreme, once prey density goes to zero, African wild dog density must also go to zero. Our study compared ecologically similar areas that varied in the degree of human-caused prey depletion, and found that African wild dogs had lower fitness in areas of low prey density, despite the benefits of low lion density. Their population growth rate was above one in areas with higher prey density (despite more lions), and below one in areas with fewer prey (despite fewer lions).

The decline of large herbivores across sub-Saharan Africa is fundamentally changing the processes that limit African wild dogs, and prey depletion is becoming a binding constraint on population growth. For African wild dogs, this change creates new problems and demands new priorities for conservation. If prey availability is beginning to limit African wild dogs, then efforts to protect and restore depleted prey populations are a priority across much of their range.

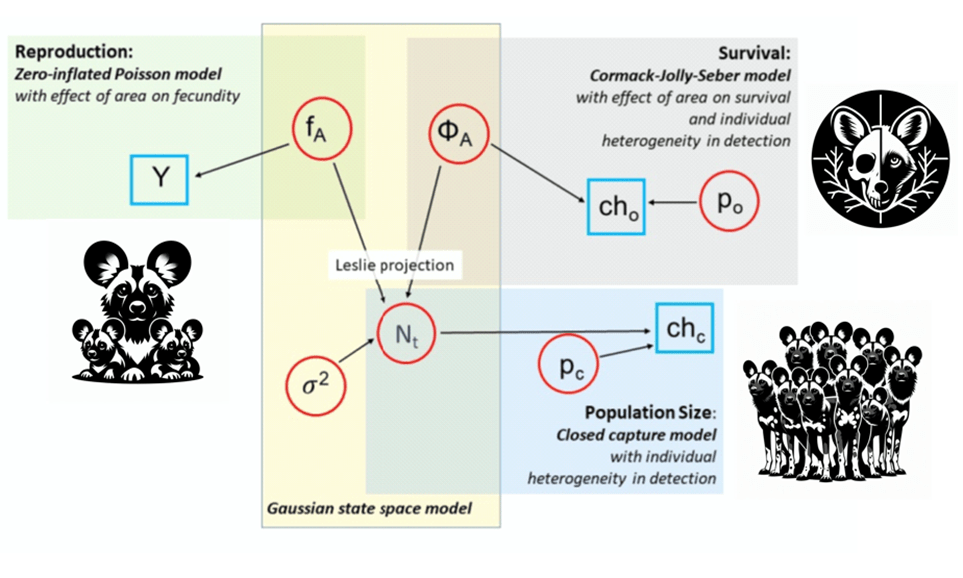

Understanding population growth and the drivers of population dynamics is the perpetual aspiration of conservation biology. In most studies of large carnivores, inferences about fitness or population growth come from the analysis of a single variable using a single data stream, for example by estimating population size using camera trap data, or estimating the survival rate using a mark-recapture model. Integrated population models (IPMs) provide a powerful tool to unify separate data sets for estimates of survival, reproduction, and population size into a joint likelihood, which allows for greater precision and consistency in inferences about the drivers of population dynamics.

We fit a Bayesian integrated population model (IPM) from long term intensive monitoring of population size, survival and reproduction for African wild dogs in the Luangwa Valley Ecosystem (LVE) of Eastern Zambia. Our study area included four areas that were ecologically similar but varied in prey density, protection level, and lion use. The IPM allowed us to estimate the local population growth rate for each area (i.e., growth due survival and birth rates without migration), and revealed cryptic source-sink dynamics. The region of lowest prey density and low lion use (due to low protection) had a consistent pattern of low survival, reproduction, and local growth rate; while the region of highest prey density (and intermediate lion use) had the highest estimated survival, reproduction, and local growth rates. Regions with intermediate prey densities had intermediate survival, reproduction, and local growth rates. This coherent pattern of bottom-up limitation has not previously been reported for African wild dogs, and we suspect that it may now be common. More broadly, many guilds are structured by competition for resources that are being depleted by human activities, and we suspect that fundamental shifts in the process that limits competitive subordinates may be widespread.

While IPMs are not a perfect tool, they can increase our ability to identify the drivers of population declines, and can provide increased confidence about our inferences when they present consistent patterns in survival, reproduction and population density. Effective conservation action, investment, and policy is dependent on good assessments of population dynamics and accurate inferences about the causes of population growth or decline. The use of quality data collected from long-term monitoring paired with IPMs has the potential to provide valuable guidance to conservation planning.

Read the full paper

Creel, S., Reyes de Merkle, J., Goodheart, B., Mweetwa, T., Mwape, H., Simpamba, T., & Becker, M. S. (2024). An integrated population model reveals source- sink dynamics for competitively subordinate African wild dogs linked to anthropogenic prey depletion. Journal of Animal Ecology, 00, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.14052