This blog post is provided by Jamie Priest, Camilo M. Ferreira, Philip L. Munday, Amelia Roberts, Riccardo Rodolfo-Metalpa, Jodie L. Rummer, Celia Schunter, Timothy Ravasi, and Ivan Nagelkerken and tells the #StoryBehindthePaper for the paper “Out of shape: ocean acidification simplifies coral reef architecture and reshuffles fish assemblages”, which was recently published in the Journal of Animal Ecology. In their study, the authors compare a healthy and an acidified coral reef, finding that ocean acidification is flattening coral reefs and reducing damselfish abundance.

Would it surprise you to learn that some fishes are quite the architectural connoisseurs? Damselfishes, perhaps the most iconic denizens of coral reefs, have strong preferences for complex coral architecture, and the finest branching corals are prime reef real estate. So, what happens when these habitats get bent out of shape? In our study, we set out to investigate how ocean acidification is flattening these underwater metropolises, and what this shift in habitat characteristics will mean for resident damselfishes.

Coral reef flattening is not a wholly novel phenomenon. It is, for example, associated with prolonged or repeated bleaching events that lead to widespread coral death, after which their skeletons eventually crumble away, or else with unusually strong erosive events such as storms. However, ocean acidification, the insidious counterpart to ocean warming, acts in far less intuitive ways to alter coral reef architecture.

It takes a lot of calcium carbonate to build a coral skeleton, and the more complex the structure of the skeleton, the higher the carbonate demand will be. In acidified conditions, this demand becomes increasingly difficult to meet, as the reduction in pH decreases the readily available carbonate ions. But for those coral species with simple, mound-like structures, which take less calcium carbonate to construct, this change in conditions can provide a welcome leg-up in competitive interactions. As pH drops, these ‘massive’ corals out-compete their struggling branching counterparts in the race for space, and can come to dominate the reef. Unlike in warming-only scenarios, where flattening is caused by coral death, this competitive shift leads to reefs where living coral cover remains high, but structure is nonetheless decimated.

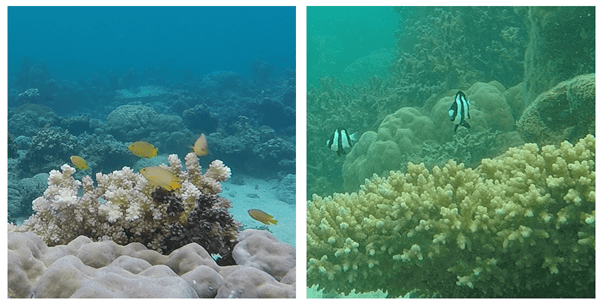

To find out what this unique mode of reef flattening might mean for reef-fish communities, we turned to a naturally acidified area of coral reef that flanks an underwater volcanic seep in Upa-Upasina, Papua New Guinea. Here, volcanic gases steadily stream from the seafloor like the bubbles in a glass of champagne. The coral reef immediately adjacent to this seep is exposed to acidification conditions that are very much like those we anticipate under future climate change scenarios, whilst a mere 500 metres away, the reef is unaffected by the seep – an incredible opportunity to directly contrast current and future-analogous conditions, side-by-side, with a full suite of ecological interactions in place.

Surveys of coral cover at both reef areas revealed, as anticipated, a substantial shift towards massive corals and a decline in complex branching corals at the seep, despite a modest overall increase in total live coral cover. But to understand what this might mean for resident fishes, we had to get a handle on their architectural whims. If fishes were selecting habitat primarily on health, choosing live corals over dead ones, the increase in live coral cover may prove a boon at the seep. If, however, they were preferencing complex structures, the decline in branching corals would represent a troublesome ecological disturbance. To find out, we set up a number of video cameras across the reef, and recorded how five different damselfish species interacted with available habitats. From these recordings, we were able to calculate the proportion of time an individual fish spent in each habitat. Our premise was simple – if a fish is using habitat randomly, the proportion of time it spends in each habitat should be approximately equal to how available that habitat is in the local area. However, if a fish spends significantly more or less time in a habitat than we would expect, then this is signal of habitat preference or avoidance.

We found that, of the five damselfish species we looked at, two selected habitats primarily on architectural characteristics, choosing branching structures over the health of the coral colony. Another two species preferred live over dead corals, and were quite content to associate with massive corals. However, these two damselfishes spent the same proportion of their time in branching habitats at the seep as they did in unacidified areas, despite their substantially reduced availability. In other words, they still sought out these complex habitats even as they became scarce, suggesting that branching corals play an important role in their daily lives. Our remaining focal species was a known rubble-specialist, and was observed associating most strongly with rubble, as expected.

So what, then, does this alteration to coral architecture mean for these damselfishes? Quite a lot, it turns out. We saw a 60% decline in overall damselfish abundance at our seep location relative to the unaffected reef. Although the effects of acidification at volcanic seeps are highly localised, climate change-driven acidification will be anything but. As an increasingly worrisome global stressor, ocean acidification holds the capacity to flatten coral reefs worldwide. Our results show that such a loss of coral structure can significantly influence the abundance of small-bodied reef fish, and foreshadows broader ecological change in future oceans.

Read the paper

Read the full paper here: Priest, J., Ferreira, C. M., Munday, P. L., Roberts, A., Rodolfo-Metalpa, R., Rummer, J. L., Schunter, C., Ravasi, T., & Nagelkerken, I. (2024). Out of shape: Ocean acidification simplifies coral reef architecture and reshuffles

fish assemblages. Journal of Animal Ecology, 00, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.14127