This blog post is provided by Heitor Sousa and Rob Salguero-Gómez and tells the #StoryBehindThePaper for the paper “Severe fire regimes decrease resilience of ectothermic populations”, which was recently published in the Journal of Animal Ecology. In their study, Heitor, Rob and colleagues found that intermediate fire regimes may be the most conducive to resistance for several Cerrado lizard species, and that variation in life history traits influences the ability to adapt to novel conditions.

Resilience in a changing world

At a time when Brazil is facing devastating fires across its territory, from the Amazon rainforests, to the Cerrado savannahs, the impact of human actions on nature is becoming increasingly evident. The Cerrado savannahs, often referred to as the “cradle of waters” of Brazil, is both one of the world’s richest biodiversity hotspots and one of its most threatened. Climate change, combined with inadequate land use management, is exacerbating a scenario of uncontrolled wildfires that directly harms biodiversity, ecosystems, and human populations. Understanding which fire regimes natural populations can endure and recover from is more crucial than ever in a world experiencing more frequent and intense fires1.

The concept of resilience in ecological systems has intrigued scientists for decades. Yet, despite much research, progress has been slow due to ongoing debates about how to define and quantify resilience. Using transient theory2,3—which doesn’t assume ecological systems are in equilibrium, unlike traditional approaches—we tested how the life histories of three Cerrado lizards (Fig. 1) relate to their resilience potential in response to climate change and varying fire regimes.

To do so, we parameterised 2,700 size-structured population models with 14 years’ worth of monthly field data across five sites historically exposed to different fire regimes. You may be wondering: “monthly individual-level data?” May seem impossible to collect such data, right? Well, not for our hard-working team that have not missed one single month of data collection since 2005 in the IBGE Ecological Reserve (RECOR), located in Brasília (Brazil’s capital – not Rio or São Paulo for the surprise of some people)!

The Fire Project

Our project is a rare and extremely valuable example of a long-term natural experiment. Initiated in 1989, this project was designed to study the impacts of fire in the Cerrado. Before that, between 1972 and 1990, the area was completely protected from fires. The experiment was groundbreaking by subjecting plots (Fig. 2) to different prescribed fire regimes (controlled burns) that occur at specific times (early, mid, or late dry season) and with varied frequencies (every two or four years). Thanks to the continuity and rigour of this project, we can better understand today how populations of native Cerrado species adapt and resist environmental disturbances, guiding more efficient and sustainable management policies.

The size-structured population models

We used stochastic Integral Projection Models (IPMs) to describe the life cycle of the three species we studied. IPMs relate the vital rates, such as survival, growth, and reproduction to a continuous phenotypic trait4, such as body size. But before building IPMs, we need to estimate the vital rates and unravel which and how environmental data and individuals’ phenotypic trait predict them. For these estimates, we used Bayesian mark-recapture models and generalised linear models. With 2,700 months x plots x species, you can imagine how much time these models took to converge… In a novel approach, we integrated in these models, microclimate and ecophysiological data to try to understand the mechanisms behind the variation of the vital rates in each population. Then, the IPM building process is relatively easy (with the help of the great ipmr package5). With the IPMs, we derived the life history traits (generation time and reproductive output)6 and demographic resilience components (resistance, compensation, and recovery time)7.

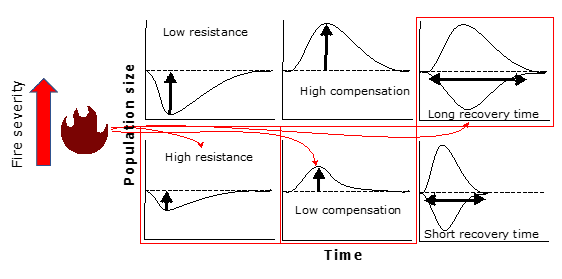

Resistance is the ability of a population to avoid a decline in numbers during a disturbance, such as a fire. Compensation is when, after a disturbance, the population not only maintains itself but even increases in size. This happens when species adapt or adjust in some way. Recovery Time refers to the time it takes for populations to stabilize their structure after going through a disturbance. These three components help measure how well a population can survive and adjust to environmental changes, such as those caused by fires and climate change.

Implications of our study

Our results revealed that while lizards are more resistant under severe fire regimes, this comes at a cost: their capacity for compensation and recovery drastically decreases (Fig. 3). The data suggest that intermediate fire regimes may be more beneficial for long-term resilience. In a period of intensifying environmental crises, our results highlight the importance of promoting heterogeneity in fire management, avoiding severe regimes, such as large wildfires, which homogenise the environment and harm fauna recovery. Furthermore, we raise concerns about the reproductive limitations of some species, especially those with longer life cycles and lower reproductive rates, which face greater challenges in adapting to these new conditions.

These findings are highly relevant for environmental management and public policy formulation, as uncontrolled fire regimes not only threaten biodiversity but also the ecological stability of key regions like the Cerrado. By better understanding how these populations respond to environmental disturbances, we have the opportunity to develop more effective strategies to mitigate the effects of climate change and fires. Thus, we conclude that while species have the potential to adapt, the tipping point for many of them may already have been reached. With that, there is a window of opportunity to reverse some of the damage, but action needs to be swift and coordinated. In times of unprecedented environmental challenges, scientific evidence points to the need for a new perspective on fire management and combating climate change in Brazil, as ways to ensure the survival of our biodiversity and the preservation of our most precious ecosystems.

Read the paper

Read the full paper here: https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.14188

Read more:

1. Bowman, D.M.J.S., Kolden, C.A., Abatzoglou, J.T., Johnston, F.H., van der Werf, G.R. & Flannigan, M. (2020) Vegetation fires in the Anthropocene. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 1, 500-515. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-020-0085-3

2. Stott, I., Townley, S. & Hodgson, D.J. (2011) A framework for studying transient dynamics of population projection matrix models. Ecology Letters, 14, 959-970. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01659.x

3. Capdevila, P., Stott, I., Beger, M. & Salguero-Gómez, R. (2020) Towards a comparative framework of demographic resilience. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 35, 776-786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2020.05.001

4. Easterling, M.R., Ellner, S.P. & Dixon, P.M. (2000) Size-specific sensitivity: Applying a new structured population model. Ecology, 81, 694-708. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2000)081[0694:SSSAAN]2.0.CO;2

5. Levin, S.C., Childs, D.Z., Compagnoni, A., Evers, S., Knight, T.M. & Salguero-Gómez, R. (2021) ipmr: Flexible implementation of Integral Projection Models in R. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 2021, 1826-1834. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13683

6. Jones, O.R., Barks, P., Stott, I., James, T.D., Levin, S., Petry, W.K., Capdevila, P., Che‐Castaldo, J., Jackson, J., Römer, G., Schuette, C., Thomas, C.C. & Salguero‐Gómez, R. (2022) Rcompadre and Rage—Two R packages to facilitate the use of the COMPADRE and COMADRE databases and calculation of life‐history traits from matrix population models. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 13, 770-781. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210x.13792

7. Stott, I., Hodgson, D.J. & Townley, S. (2012) Popdemo: An R package for population demography using projection matrix analysis. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 3, 797-802. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210X.2012.00222.x