This blog post is provided by Mark Pitt and tells the #StoryBehindThePaper for the paper “Environmental constraints can explain clutch size differences between urban and forest blue tits: Insights from an egg removal experiment” which was recently published in the Journal of Animal Ecology. The authors find that urban blue tits lay fewer eggs than their non-urban counterparts, possibly as a response to limited resources.

The urban environment

Cities and towns are familiar habitats to us humans, with the UN estimating that 68% of the human population will live and work in urban spaces by 2050. However, urban environments are challenging to navigate: they are fragmented spaces, characterised by increased disturbance and pollution, alongside a high abundance of non-native species. Despite the apparent ability of species to inhabit urban habitats, it is critical to understand whether they are adaptively responding to, or are constrained by, the challenges of city life.

Birds and urbanisation

Birds are arguably the most common species encountered in our cities and towns. Thanks to their strong dispersal capabilities, birds are less likely to be constrained in urban habitats compared to other taxa. Instead, they might avoid urban spaces entirely or adapt to them and, potentially, even exploit the new opportunities provided. Despite the challenges, urban areas bring several benefits, including stable food sources, warmer ambient temperatures, and a reduced abundance of predators, making them attractive environments to some generalist species (Figure 1).

Urban bird populations seem to be relatively consistent in the traits they exhibit. Compared to their non-urban counterparts, urban birds tend to be smaller, have more generalist diets, sing shorter songs at higher frequencies, and forage over smaller geographic regions. One of the most widespread responses is that urban birds consistently lay fewer eggs than their non-urban counterparts. Yet, we still have a poor understanding of why urban birds lay fewer eggs.

Why do urban birds lay fewer eggs than their non-urban counterparts?

It could be that urban females face constraints from the urban environment when laying, being unable to source enough nutrients to produce more eggs. Small songbirds need to source the energy and nutrients for egg formation almost daily during the laying period – an incredibly demanding task. Most of these nutrients are sourced from invertebrates, including caterpillars, spiders, and snails. However, invertebrate abundance is generally low in cities, so urban birds may compensate by foraging on food waste and bird feeders. While plentiful, human-provisioned food is generally of poor quality. Therefore, under this constraint hypothesis, urban birds may be producing as many eggs as they can given the limited availability of resources.

Alternatively, it could be that urban birds lay fewer eggs as an adaptive response to city living. Here, by laying fewer eggs, urban birds may increase their chances of recruiting more of their young into the population than if they continued to lay as many eggs as their non-urban neighbours. Therefore, urban parents may be pre-empting the limitations of the urban environment, producing a small clutch to adaptively match the number of offspring they can adequately rear to independence.

Our questions and methodology

To this end, we wanted to understand why blue tits breeding in a park in Glasgow laid fewer eggs than those in an oak woodland 40 kilometres away on the shores of Loch Lomond. Is this an adaptive response from the urban birds? Or is it a result of the urban birds being constrained during the laying period?

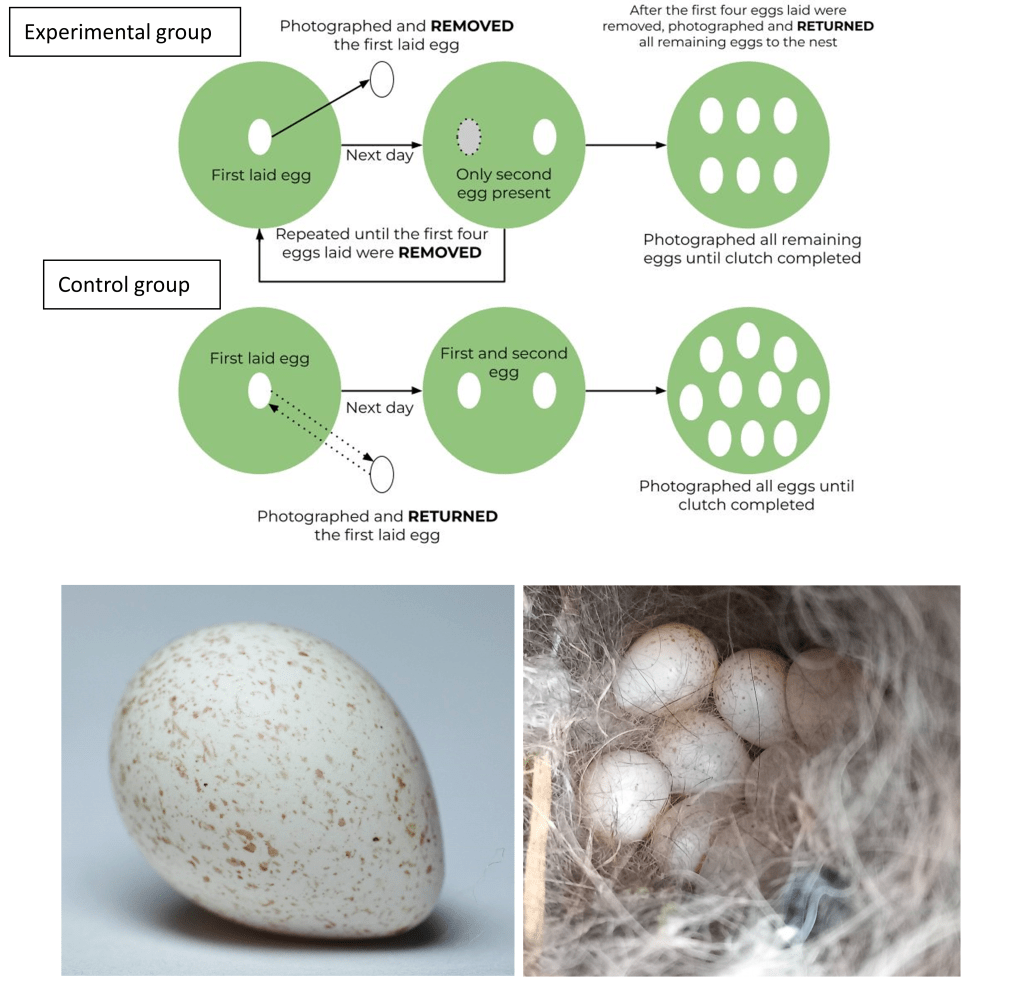

Our study builds on several previous egg removal experiments which have been used to experimentally manipulate egg production in birds. In egg removal experiments, it has been shown that blue tit females produce two additional eggs following the removal of the first four eggs. Thus, if the number of eggs blue tits lay in urban habitats is constrained by the urban environment, we expected urban females to produce fewer, or no, new eggs after egg removal when compared to the non-urban population. If urban blue tit females are not constrained during egg laying, with their small clutches potentially being an adaptive response to urbanisation, we predicted that both urban and non-urban females would lay new eggs after egg removal to keep as close as possible to the optimal clutch size for their respective habitats. Therefore, in a single breeding season in 2022, we removed the first four eggs laid in the experimental nests of urban and forest blue tits and observed how the birds responded to this manipulation (Figure 2).

Our findings

Overall, our results are most in line with the constraint hypothesis. Urban birds did not lay as many new eggs following egg removal when compared to their non-urban counterparts – with there being an average of 0.36 new eggs in urban nests compared to two eggs in forest nests. If urban birds were not constrained in some way during egg production, then they should have laid as many eggs as non-urban birds to maintain their optimal clutch size. Therefore, our findings indicate that urban blue tit females experience greater energetic or nutrient constraints when laying, limiting how much they can invest in egg production.

Interestingly, despite the experimental reduction in clutch size in urban experimental nests, there was no difference in the number of fledged offspring between the urban treatment groups (egg removal nests versus control nests). This is surprising as it suggests that urban control birds produced more eggs than the number of offspring they could successfully rear to independence. Thus, suggesting the clutches of urban birds may not be optimally fine-tuned to the urban environment. It is possible that the continued dispersal of urban birds between urban and non-urban habitats might be preventing the evolution of an adaptive urban clutch size by homogenising gene pools between urban and non-urban habitats.

By studying how different species respond to city life, we can better predict the impacts of urbanisation on species persistence and capacity for adaptative evolutionary change. As urban areas expand, ensuring they remain viable habitats that support wildlife is an increasingly important challenge to mitigate biodiversity loss.

About the author

I am a second year PhD student at the University of Glasgow, studying intergenerational effects of parental age in two-spotted field crickets (Gryllus bimaculatus). Most of my background, however, has been investigating how birds respond to anthropogenic environmental change, including urbanisation and climate change, mostly focussing on how this influences their reproductive success and capacity for adaptive evolutionary change.

Read the paper

Read the full paper here: Pitt, M. D., Alhowiti, N. S. S., Branston, C. J., Carlon, E., Boonekamp, J. J., Dominoni, D. M., & Capilla-Lasheras, P. (2024). Environmental constraints can explain clutch size differences between urban and forest blue tits: Insights from an egg removal experiment. Journal of Animal Ecology, 00, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.14171