This blog post is provided by Charlotte Taelman and Garben Logghe and tells the #StoryBehindThePaper for the paper “Unravelling arthropod movement in natural landscapes: small-scale effects of body size and weather conditions”, which was recently published in the Journal of Animal Ecology. Together with colleagues, they track and study the ability of over 200 insect species to find their way home.

Home is a place where you feel at your best, where you feel safe, and where everything feels familiar. We associate our homes with places where we can eat, sleep, and have a good time. However, when we are exposed to new conditions, where nothing feels familiar anymore, and where it might be more difficult to find food or a place to sleep, we long for our homes more than ever.

Humans are not alone in this regard. We found the same behaviour in insects.

We often believe that because insects have tiny brains, they can’t really think, or make decisions based on accurate reasoning. We usually associate these animals with having a passive lifestyle, where they live according to the conditions around them without being fully aware of what is going on.

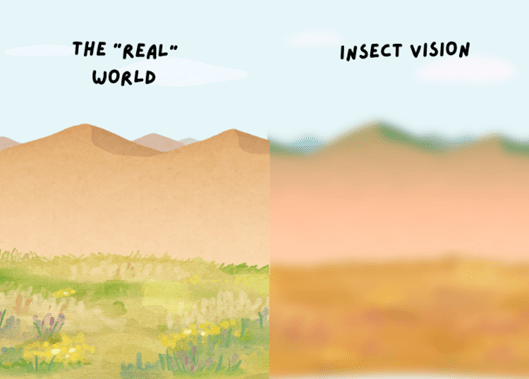

In light of this reasoning, we sometimes assume that insects don’t perceive their environment very well, and that they are not able to distinguish between patches of suitable areas within a larger landscape of poor-quality environments. In landscape ecology these types of environments are respectively referred to as habitat and matrix. As a consequence, we expect insects to fail at recognizing their habitat from afar when (accidentally) taken out of it (Fig. 1). For a long time, we also assumed that insects passively end up in suitable environments by simply using the currents of the winds, and that active decision-making based on information from the environment is pretty much non-existent.

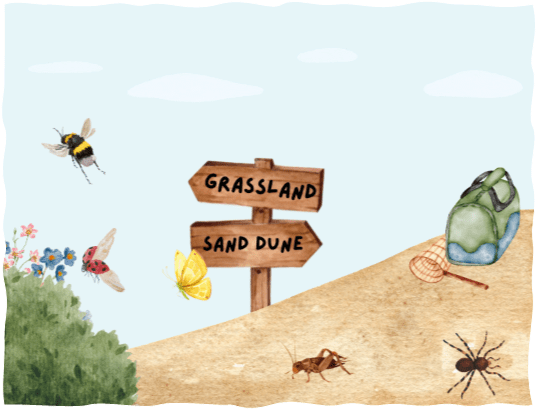

These assumptions have actually never been tested for insects at a landscape scale! Therefore, we decided to go out in the field and test this “habitat recognition” on a bunch of insect species. We went looking for all kinds of species in a highly diverse dune grassland, bordering on a large sand dune with very little vegetation and designated these two areas as habitat and matrix, respectively (Fig. 2).

We caught all individuals sitting on plants, flying around and resting on the ground. We took them individually to the sand dune where we released them after a few minutes of waiting. We followed their behaviour closely and watched where they were going. In total, nearly 1400 individuals, covering more than 200 species, were captured and released in this field experiment.

Surprisingly – most of the captured individuals, the flying ones in particular, deliberately moved back to where they were caught (Fig. 3). In addition to the release of the individuals, we measured the speed and the direction of the wind each time we set an individual free. We initially thought that wind directions opposite to the direction of the habitat might cause a bias in the actual movement, as they would hinder movement towards a suitable area. It turns out that stronger opposite winds indeed lowered the chances of moving towards the grassland, but that it did not prevent overall movement towards the habitat.

Our investigation has revealed that our initial assumption about insects is thus very wrong. They are not passive creatures at all when it comes to moving between high and low-quality areas in the landscape. They can make a very accurate guess of where their environment is located when they are taken out of it, and further move successfully towards it. In many cases, we even saw bumblebees flying in an exploratory circle for a few seconds, before setting off towards the grassland. This proved that the landscape can be perceived by these individuals, and guides them in the decision-making of where to go.

This study has shown that the assumptions we make about arthropods are not necessarily true, and testing in the field is necessary to avoid further misconceptions about the most diverse group of species on earth. The question remains: which other characteristics in insects are still unknown or widely misunderstood?

Read the paper

Read the full paper here: Logghe, G., Taelman, C., Van Hecke, F., Batsleer, F., Maes, D., & Bonte, D. (2024). Unravelling arthropod movement in natural landscapes: Small-scale effects of body size and weather conditions. Journal of Animal Ecology, 93, 1365–1379. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.14161