This blog post is provided by Joe Wynn, and tells the #StoryBehindThePaper for the article “Selective disappearance based on navigational efficiency in a long-lived seabird“, which was recently published in the Journal of Animal Ecology. Together with colleague, Joe studies improvements in migratory performance with age in common terns and find that improvements are due to selective disappearance of less efficient navigators rather than learning, raising intriguing questions about evolutionary and pre-breeding processes.

When we think about how animal behaviour changes with age, we often have the rather optimistic view that improvements must represent learning. Nowhere is this more true than when considering the long-distance migration of long-lived seabirds, and it has been repeatedly suggested that these birds might improve their migratory performance through year-on-year increases in experience. I mean: how can migratory performance be better in older birds without the birds themselves learning to migrate better?

Changes with age, however, could just as easily reflect ‘selective disappearance’ based on the migratory phenotype, rather than learning. In this scenario, birds might be fixed in their migratory abilities, with this fixed ability predicting their probability of surviving another two journeys, and therefore another year. Rather morbidly, this would mean that older birds still are better migrants, but that this is only true because the less good migrants, that would still be present among the young, are already dead.

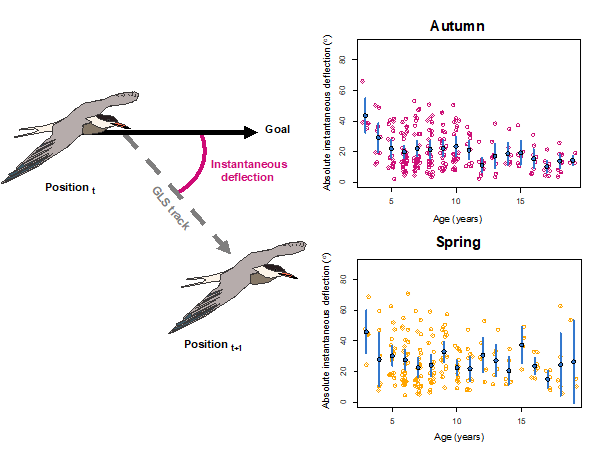

Testing whether improvements in navigational performance with age reflect learning or result from selective disappearance is no easy feat, because it requires (i) collecting several migratory tracks per bird, for a sufficiently large group of birds of known age, and (ii) knowing how to quantify navigational performance. Luckily for us, we could do this making use of data obtained as part of our long-term tracking study of common terns breeding at a mono-specific colony in Wilhelmshaven, Germany. These relatively long-lived seabirds are not only highly site-faithful to this breeding colony, but also overwinter in individual-specific areas. This means we know exactly where these birds aim to go with every migratory journey we observe, and can test how efficiently they do so.

To test whether changes in navigational efficiency with age reflected selective disappearance or learning, we partitioned the variance in this trait into its between-individual and within-individual components. This sounds complicated, but really just means being able to tell the difference between learning and selection statistically. When we did this, we found that there was no measurable learning going on, at least between the ages of 3 and 22, and that all variation with age was caused by selective disappearance of breeding birds that did not navigate efficiently. Given that we also found that birds who migrated efficiently arrived earlier and had shorter migrations, our analyses might even hint at the mechanism upon which selection might act.

As such, we (rather sadly) conclude that – amongst breeding adult common terns – all observed changes with age appear to be selective. This might lead us to ask some interesting follow-up questions. Is there learning prior to birds starting their breeding careers? What are the consequences of selective disappearance of poor navigators? Is the ability to navigate heritable? And could this effect drive evolutionary processes? These are, however, questions for another day…

Read the paper

Read the full paper here: Wynn, J., Kürten, N., Moiron, M., & Bouwhuis, S. (2025). Selective disappearance based on navigational efficiency in a long-lived seabird. Journal of Animal Ecology, 00, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.14231

One thought on “Only the inefficient die young: how selection drives changes in migration efficiency with age”