This blog post is provided by David Lopez-Idiaquez and tells the #StoryBehindThePaper for the article “Global patterns of colouration complexity in the Paridae: effects of climate and species characteristics across body regions”, which was recently published in Journal of Animal Ecology. In this study, Lopez-Idiaquez explored the colouration of specimens of 58 Paridae species, and found that distinct plumage areas are affected by different environmental and social variables.

The diversity of bird colouration is remarkable. Some species have a dull, monochromatic plumage, while others are bright and multicoloured. Scientists have been intrigued by this variation since the 19th century, when naturalists like Darwin, Wallace and von Humboldt documented the wide range of colorations exhibited by the birds they encountered during their travels across the world.

Originally, the presence of species with bright colours puzzled scientists. These vivid colours seemed to contradict Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection, as those conspicuous traits attract predators, jeopardising the chances of survival of the individuals displaying them. Darwin himself was troubled by this problem, expressing his frustration in a letter to the American botanist Asa Gray, in which he wrote:

“The sight of a feather in a peacock’s tail, whenever I gaze it, makes me sick!”

It wasn’t until Darwin proposed the theory of sexual selection in 1871 that scientists began to understand how such striking traits could evolve. Nowadays, we know that plumage colouration serves a variety of functions, ranging from camouflage to signalling individual quality to potential mates. Consequently, the evolution of plumage colouration is driven by a combination of natural and sexual selection.

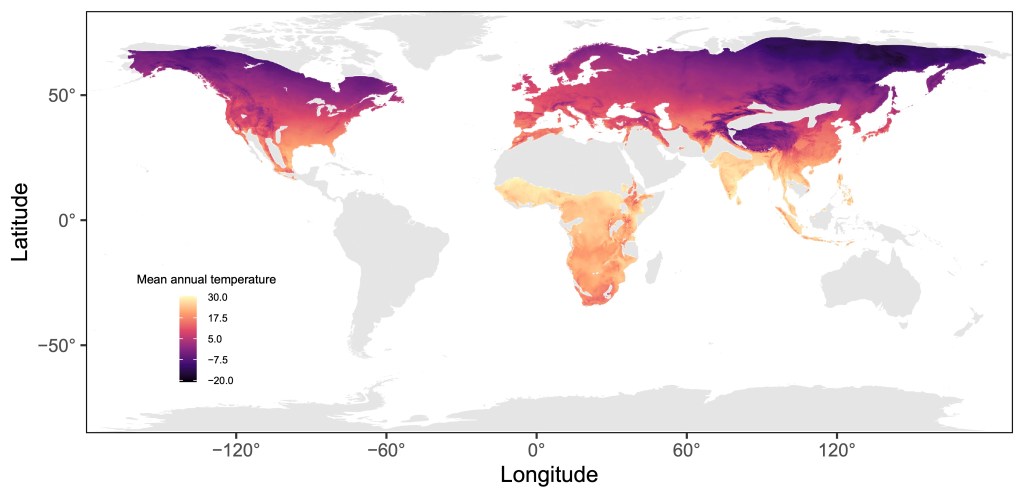

Recent studies have focused on identifying the ecological factors that drive variation in plumage colouration across species. These studies have shown that colouration is linked to factors such as temperature, precipitation or the diversity of the communities the species inhabit. These links likely arise because those environmental factors influence the strength of both sexual and natural selection acting on plumage colouration.

After reading these studies, I realised that an important question remained unanswered: Do the ecological factors that influence the evolution of colouration vary across different areas of a bird’s plumage?

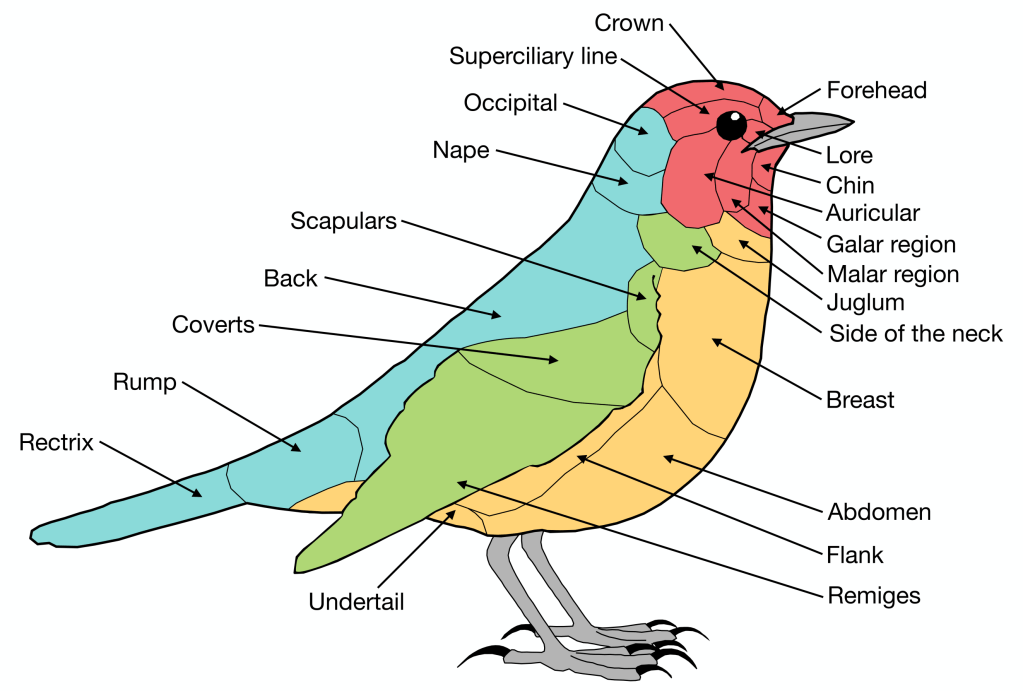

Because different plumage areas serve different functions, it is reasonable to expect that their colouration can be sensitive to different environmental variables. For instance, plumage on the head and chest is often involved in signalling quality, whereas back plumage is more commonly associated with camouflage and thermoregulation.

This divergence in the function of different plumage patches suggests that they may be subject to different evolutionary pressures and, thus, influenced by different environmental variables. Therefore, to understand the diversity of colourations observed across bird species, it is essential to analyse individual plumage patches separately.

To carry out this research, I benefited from the outstanding bird skin collection at the Natural History Museum in Tring, which houses more than 750,000 specimens representing 95% of all living bird species.

I focused on the species within the Paridae family, which includes most tits, chickadees and titmice. This group is very suitable to address my research question because its members are widely distributed across the world, thus experiencing a wide range of environmental conditions. Paridae species also show considerable variation in plumage colouration. Some are quite uniform, while others are much more variable, as illustrated in the figure above.

In total, I measured 22 different plumage patches of six specimens (three males and three females) from 58 Paridae species. Since each patch was measured three times per specimen, this resulted in more than 22,500 colour measurements!

Using this data, I calculated the colour complexity of each species, a measure of how diverse a species’ plumage colours are. I did this by considering both the whole plumage and four separate plumage areas.

For each species, I also gathered data on several biotic (e.g. morphology, sympatry with other Paridae and predators or sexual dichromatism) and abiotic factors (e.g. mean temperature and precipitation and their variability) to analyse how these factors influenced the colouration in each plumage area.

The results I obtained after analysing this data show that sexual dichromatism, a proxy of sexual selection intensity which represents how different the colours of males and females are, was positively associated with colouration in the four patches. In other words, species in which males and females differed more in their colouration exhibited a greater diversity of colours across patches. This suggests a widespread influence of sexual selection on colouration across the different areas of the plumage.

In addition, I found that environmental variables linked to camouflage and thermoregulation were more strongly associated with the coloration in the back and wing than in the chest and head. Conversely, environmental factors associated with resource availability were more strongly associated with the colouration of the head and chest.

Overall, these results suggest that the colouration of different parts of the birds’ plumage respond to different environmental factors, likely because of their different functions. Thus, considering different plumage patches when analysing the evolution of plumage colouration may offer insights that might be overlooked when considering the whole plumage as a single unit.

Finally, although I have written this text in the first person, this work is the result of a collaboration with Claire Doutrelant and Peter B. Pearman, who provided invaluable support throughout the development of this project.

Read the paper:

Read the full paper here: https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1365-2656.70077