This blog post is provided by Kevin White and tells the #StoryBehindThePaper for the article “Life-history trade-offs and environmental variability shape reproductive demography in a mountain ungulate“, which was recently published in Journal of Animal Ecology. This study explored how life-history trade-offs and environmental variability influence demography of mountain goats in extreme environments.

Living on a steep mountainside, blanketed in snow nine months of the year, hardly seems like a good place to make a living – let alone raise kids. Yet, for an extraordinary array of alpine specialists adapted for life in extreme conditions, stout challenges are a part of life. Adaptations are diverse, often comprising both morphological and behavioral mechanisms. Hibernation, a thick wooly coat, snowshoe-like feet, and cryptic white coloration provide but a few of the diverse, higher-profile solutions to the physical challenges of often cold, mountainous environments.

Less obvious, though not less important, are life-history strategies – the way in which individuals balance energy use among growth, reproduction and survival. How organisms adjust their relative investment in these components to optimize fitness is fascinating, oftentimes complex, and in extreme mountain environments, difficult to study. Yet, such knowledge is pressing, as mountain ecosystems are changing rapidly and effective conservation requires a sound understanding of population ecology processes.

We studied mountain goats – a sentinel species of alpine environments with high cultural and ecological value – in coastal Alaska. They reside in rugged and dynamic mountain environments. Heavy weather is the norm, glaciers cloak summits, deep snow fills alpine basins, and snow avalanches careen down steep slopes in winter. Summers are productive but short, often cool and rainy, though deleterious heat spells occur and bring physiological challenges for cold-adapted mountain species. Seasons are intertwined, with energetic reserves – built up over summer – being critical for survival over winter, as well as for carrying a pregnancy to term by late-spring. Once born, offspring require mothers to invest substantial energetic resources for milk production, a process that requires careful budgeting of energy stores that are also critical for survival during the upcoming winter – or carrying over for reproduction the following year.

Long-term study unlocks life-history ecology

Our research, now published in the Journal of Animal Ecology, was long-term, spanning over a 17-year period and across three different study areas in coastal Alaska. We captured and marked animals using a helicopter, and monitored individuals at frequent intervals from a fixed-wing aircraft (collecting observations with aid of powerful, image-stabilizing binoculars). Over time, detailed longitudinal records of reproduction and survival were compiled across multiple years to catalogue key life-history details.

We used these hard-won data to test hypotheses using generalized linear mixed models, and simulated climate effects on population growth rate through implementation of matrix population modelling. Our goal: to unlock key details about life-history ecology and climate-linked drivers of reproduction among mountain-adapted wildlife.

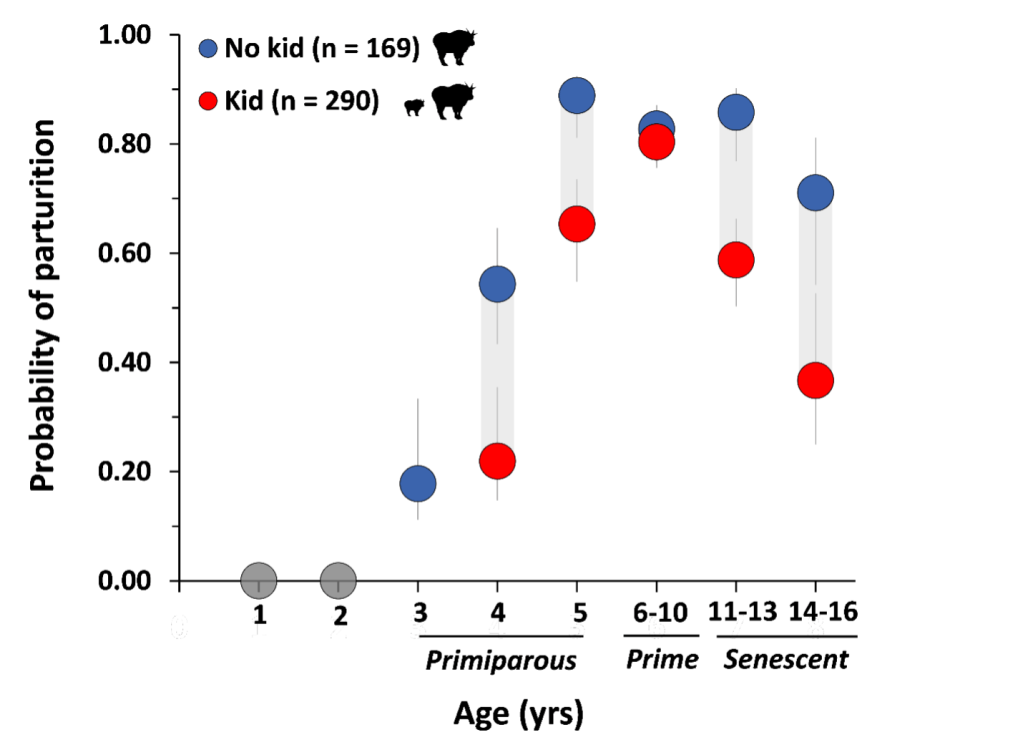

Extreme alpine conditions mean mountain goats grow slowly and reach reproductive maturity at a relatively late age. Mothers typically gave birth for the first time at four or five years of age, one to two years later than most other ungulates of similar body size. The costs of reproduction are also high, with such ‘primiparous’ females more often skipping reproduction the year following their first births, as compared to prime-aged females (6-10 years old). In fact, costs of reproduction are negligible for prime-aged mothers but at older ages (11-16 yrs) reproduction declines, with costs increasing as they begin to experience senescence. Interestingly, while giving birth imposed a cost to reproduction for young and old mothers, it did not affect their likelihood of survival or that of their offspring (over summer).

These patterns were similar to other mountain ungulates. Namely, we determined that mountain goats exhibit a conservative reproductive strategy that prioritizes survival at the cost of reproduction. This provides a risk-averse strategy well suited for optimizing fitness in variable, often extreme, mountain climates.

Mountain sentinels, climatic variability and uncertain futures

Mountain goats are climate-sensitive and considered barometers of change in alpine ecosystems. Reproductive performance was sensitive to both winter snow and summer temperature, with impacts significantly altering population growth across the range of observed conditions. Winter snow, however, is approximately twice as influential as summer temperature in shaping reproductive demography. Deep snow, for instance, buries food and increases energetic costs of movement, ultimately stealing away nutritional stores that might otherwise be allocated for reproduction. Warm summer temperatures increase physiological stress, alter behavior and constrain foraging efficiency, leading to reduced accumulation of energetic stores necessary for reproduction.

The way variation in winter and summer climate influence reproduction parallel previously documented effects on survival, carrying important conservation implications given projected changes in future mountain climate. The extent that life-history strategies can adapt and mitigate future changes in climate will likely play a key role in future productivity and viability of iconic mountain ungulate populations, and the ecological and human communities that depend on them.

Read the paper:

https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1365-2656.70137