This blog post is provided by Friederike Clever and tells the #StoryBehindThePaper for the article “Dietary resilience of coral reef fishes to habitat degradation“, which was recently published in Journal of Animal Ecology. This study investigates the degree to which dietary shifts in coral reef fish can buffer against the effects of habitat degradation.

Fishes living on coral reefs under climate change conditions face fundamental changes to their habitats. While on healthy reefs stony corals form complex architectures with plenty of hiding space (think all the holes, caves, crevices and interstices) that support millions of species, reefs impacted by global environmental change compounded by local stressors are a very different habitat. Mass coral mortality has transformed many healthy complex reefs into flatter, simpler seascapes where disturbance-tolerant taxa such as many algae and sponges mostly thrive. On degraded reefs, fishes may not find the same food in the same places anymore and exploiting alternative prey presents new challenges.

As coral cover declines, prey communities reorganize: corals and coral-associated prey may become less available while other groups may become more common. Organisms can either consume alternative prey, or move looking for their prey to cope with changes in their environment. As an immediate response, individual fish may change their feeding behaviour if they can when preferred food resources become scarce but it can alter energy intake and, ultimately, their health in ways that remain poorly known.

Our study used an interdisciplinary approach combining metabarcoding, otoliths (earbones that record growth) analysis, a length–weight–based condition factor, and reef surveys to address three questions: (i) do fishes change their diets across reefs with different coral cover; (ii) do dietary changes affect fish body condition and growth; and (iii) do individuals of the same species play different functional roles on degraded and more healthy reefs (intraspecific variation).

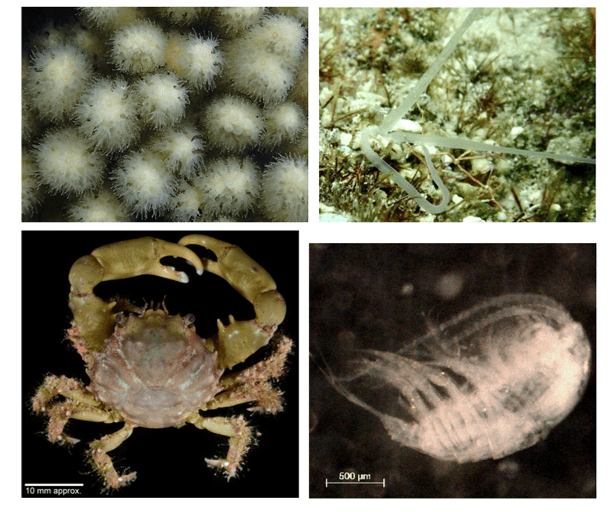

We analysed the diets, body condition and growth rate of two common, small coral reef fish species that both feed on prey living on the seafloor on coral reefs, but in different ways: a butterflyfish (Chaetodontidae) that continuously swims looking for sessile invertebrates, including corals, and a hamlet (Hypoplectrus spp.) that mostly sits and waits to hunt crustaceans and small fish – across 9 discrete Caribbean reefs ranging from high, low, and near-zero coral cover. We leveraged DNA-metabarcoding, a molecular method that allows identifying prey taxa to the species level which conventional visual analysis cannot do.

We found flexible diets for both species. Butterflyfish on relatively healthier reefs, included more corals in their diet. In contrast, on degraded reefs they fed primarily on spaghetti worm tentacles (terrebelid annelids) and showed significantly more variable body condition. Hamlets displayed a diet shift from larger crustaceans on healthier reefs to smaller prey (calanoid copepods) on degraded reefs, and the consequences of these shifts were size-specific: larger individuals were in poorer condition on degraded reefs.

The feeding flexibility (the ability to use a wide range of prey) that we observed suggests that these fish can cope with changing resource availability as habitats decline. Yet not all diets are equal: prey may vary in nutritional value and energetic costs may differ depending on the effort needed for obtaining and handling different types of prey. As coral loss gives way to algae- and rubble-dominated habitats, some invertebrate prey may become more abundant; on the flipside, community composition can change in ways that alter prey suitability for fish consumers. Ultimately, whether flexibility helps or harms depends on the balance between prey availability, quality, and the energy required to obtain it.

The different diets we found on healthier versus degraded reefs place fishes in different positions in the food web. If individual fish can switch prey over very small distances, as in Bahía Almirante, the same species may act as a corallivore in one patch and as an annelid feeder in another—thereby playing very different functional roles. This suggests that fish feeding groups or “guilds” are more fluid and less stable than commonly thought. Variation in diet implies more than just alternative prey for fish: it can reconfigure how energy flows through ecosystems with consequences for their functioning and responses to habitat change.

Read the paper here:

https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1365-2656.70196