This blog post is provided by Sofía Ten and Francisco Javier Aznar, and tells the #StoryBehindThePaper for the article “Long-term trends of epibionts reflect Mediterranean striped dolphin abundance shifts caused by morbillivirus epidemics”, which was recently published in the Journal of Animal Ecology. This study explores the epidemiology of dolphin morbillivirus (DMV) and the potential of epibiotic crustaceans to indicate shifts in striped dolphin population abundance caused by DMV.

The striped dolphin (Stenella coeruleoalba) is the most abundant cetacean in the Mediterranean Sea but faces many human-related threats, including pollution, accidental capture and reduced prey availability. It has also been heavily affected by dolphin morbillivirus (DMV), which can cause severe epizootics. Two major DMV outbreaks unleashed in the western Mediterranean and spread eastward in 1990 and 2007, but the death toll of dolphins, thus the population impact, could not be determined. Evidence does show that the first outbreak mainly affected adults and led to a sharp drop in group size, with later field surveys suggesting that the population could have partly recovered. The second outbreak affected mostly juveniles and could have caused fewer deaths according to stranding data.

Challenges to investigate DMV impact and trends

Understanding the impact of DMV on striped dolphins is difficult because population data are limited and disease dynamics is complex. The spread and severity of infection depend on many interacting factors, including population density, immunity, and genetics, as well as environmental conditions and human pressures. In addition, reliable estimates of population size before and after outbreaks are scarce and difficult to compare because surveys have used different methods and spatial coverage. Information from stranded animals did help to assess mortality, but it is also biased since a small and unrepresentative portion of the population, covering particular age groups or health conditions, reaches the shore.

Crustacean epibionts to measure DMV impact on striped dolphins

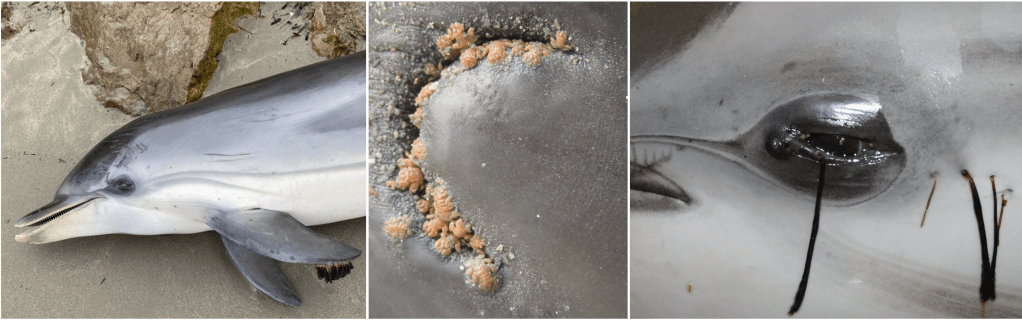

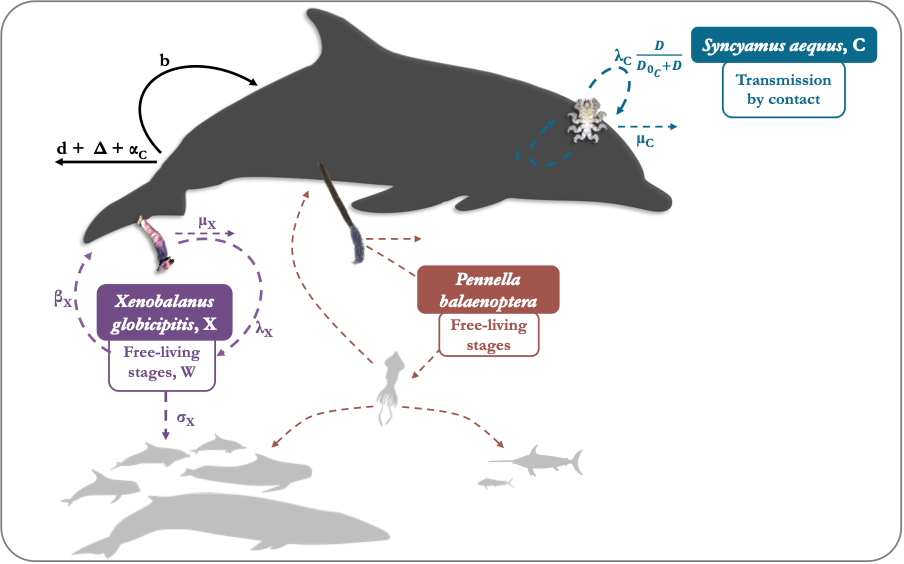

Evidence from the 1990 outbreak suggests that epibionts could serve as indicators of disease impact; stranded dolphins showed unusually high levels of two epibiotic crustaceans: the barnacle Xenobalanus globicipitis, common on cetaceans, and the copepod Pennella balaenoptera, parasitic on cetaceans and large oceanic fish. It is likely that DMV caused immunosuppression and reduced mobility, making infestation by these epibionts more likely.

In this study, we investigated whether long-term data (46 years) on the presence of these two epibionts, as well as the ‘whale louse’ Syncyamus aequus – a parasitic amphipod highly specific to striped dolphins – could provide information about the impact of DMV.

We found that Xenobalanus globicipitis and, especially, Syncyamus aequus, experienced a sharp drop in their occurrence after 1990, followed by a partial recovery; and a milder drop after 2007, succeeded by a steep population rise. Since these two epibiotic species are more specific to striped dolphins as hosts, we interpret that the concordant trends reflect shifts in the abundance of striped dolphins after DMV outbreaks. In contrast, the presence of the more generalist parasite Pennella balaenoptera on striped dolphins did not change over the decades, likely because the population of this copepod was sustained by other hosts (other cetaceans and oceanic fish).

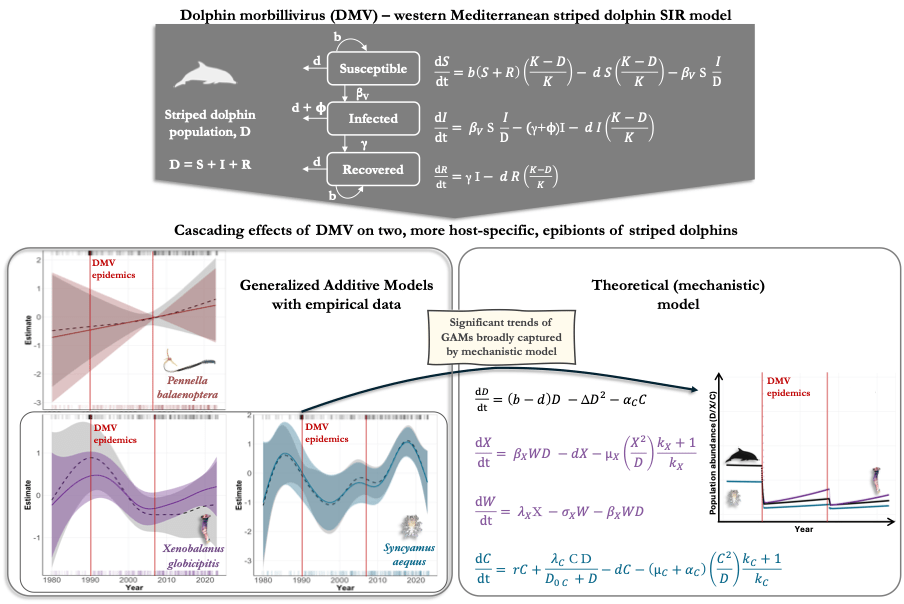

Building a DMV epidemiological model

We developed a Susceptible-Infected-Recovered (SIR) model to investigate DMV dynamics. Although the data needed as model inputs are scarce (e.g., population abundance, DMV-induced mortality or transmission rate), the model captures the most relevant trends: namely, a striped dolphin population drop after 1990 followed by an unquantified recovery, and a smaller population loss in 2007 and subsequent recovery. We tested the numerical results of the SIR model using a mechanistic model of the dolphin-epibiont populations (similar to the Lotka-Volterra predator-prey model) and observed the cascading effects of DMV-induced striped dolphin loss on the epibionts Xenobalanus globicipitis and Syncyamus aequus.

More data derived from surveys of striped dolphin abundance and DMV serology will increase the accuracy of this SIR model, potentially leading to predictions on the population impact of future DMV outbreaks.

The authors sincerely thank all members and volunteers of the Valencian Stranding Network, whose efforts made this long-term study possible.

Read the paper:

https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1365-2656.70216