This blog post is provided by Angus Mitchell, Chloe Hayes, Erick Coni, David Booth, and Ivan Nagelkerken, and tells the #StoryBehindThePaper for the article “Tropical fishes can benefit more from novel than familiar species interactions at their cold-range edges”, which was recently published in the Journal of Animal Ecology. In their study, Mitchell and colleagues investigated the challenges faced by tropical fish shifting their ranges in one of the fastest-warming marine regions on Earth.

As oceans warm, tropical fish are on the move. Many tropical fish species are extending their ranges into cooler, temperate waters. But unlike tourists on a short holiday, these fish don’t return home. They colonise new environments where they face unfamiliar habitats, predators, and competitors.

The big question is: will they thrive or struggle in their new homes?

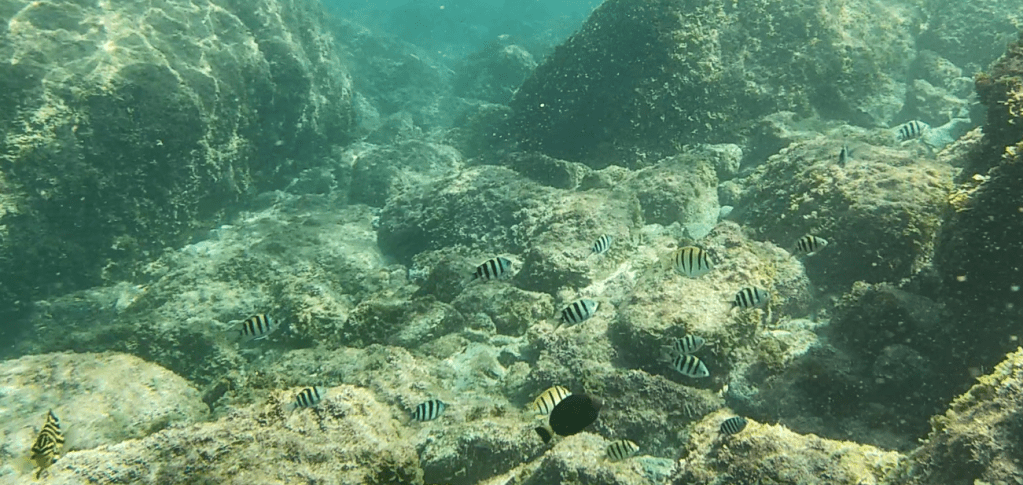

In our new study, published in the Journal of Animal Ecology, we tracked the behaviour of juvenile tropical fish along a 2,000-kilometre stretch of Australia’s east coast, one of the fastest-warming marine regions on Earth, as they moved from tropical reefs into the cooler, temperate waters at the southern edge of their range.

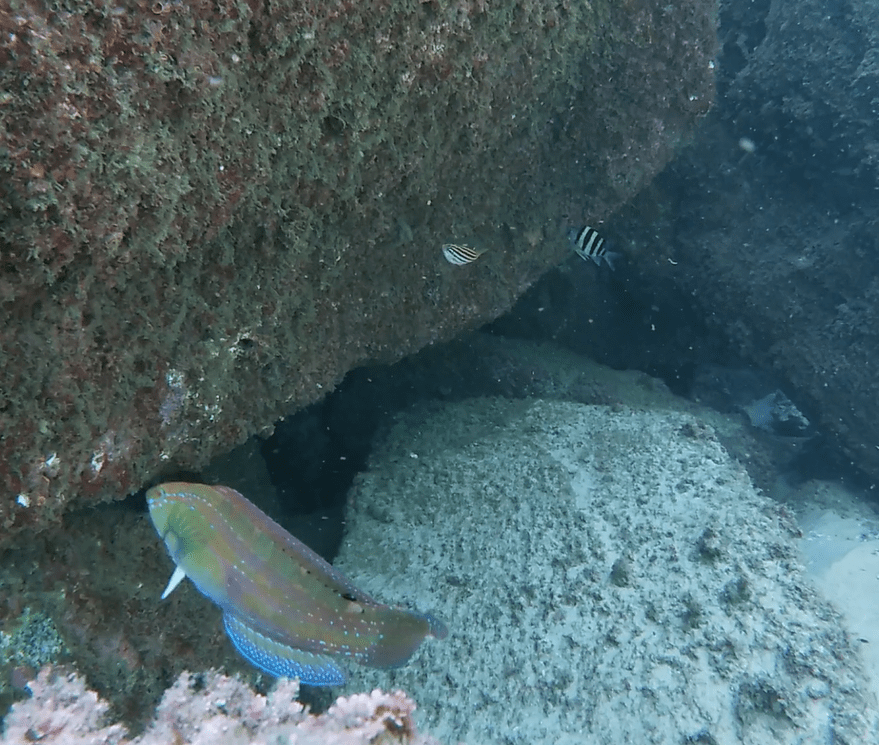

We found that tropical fishes acted very differently in these novel temperate environments. At their cold range edges, they became more cautious, spending more time sheltering and less time feeding. This shift in anti-predator behaviour likely helps them avoid unfamiliar threats, but it comes at a cost: less energy available for growth and survival.

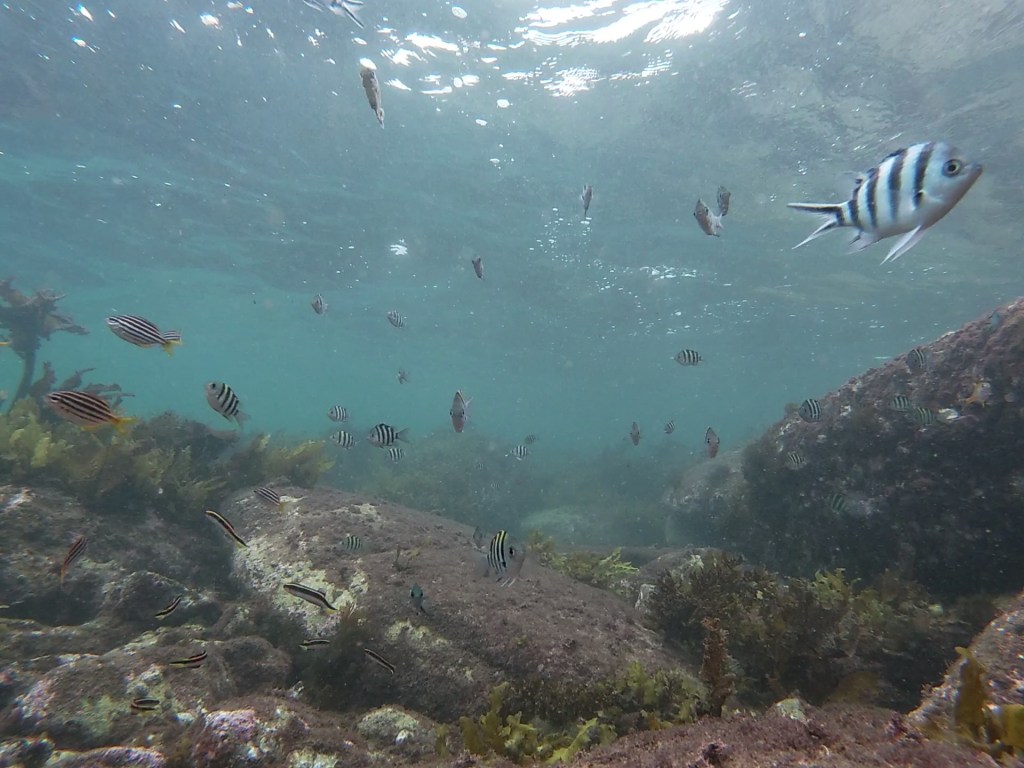

Here’s the twist. Previous studies have shown that tropical fish which shoal with local temperate species tend to survive longer and grow larger on temperate reefs, but the reason why was unclear. Our study reveals that mechanism. When tropical fish shoal with temperate fish, their behaviour changes dramatically. Three of the five tropical species we studied including the Indo-Pacific sergeant fed more often and spent less time sheltering in these mixed-species shoals. Simply put, they performed better with unfamiliar neighbours than when surrounded by their own kind.

This unexpected result suggests that novel species interactions, often assumed to be stressful or competitive, can benefit some range-extending species. Shoaling with locals may help tropical fish learn about new predators, food sources, and environmental cues. This reduces uncertainty and boosts survival in unfamiliar ecosystems.

But not everyone benefits. In the subtropics, temperate fish suffered: they were more likely to flee and fed less when tropical species were present, particularly at the warm trailing edges of their ranges. Subtropical reefs already sit at the upper thermal limit for many temperate fish. Added stress from tropical competitors could tip them over the edge. As warming continues and tropical species move further south, the combination of heat stress and negative species interactions may accelerate the decline or local disappearance of some temperate species from their historical ranges.

Overall, our findings show that climate-driven species redistributions are not just about temperature. They are also about the new relationships formed in recipient ecosystems. Some tropical fishes appear surprisingly well-equipped to adjust to life in new environments, not just through physiological tolerance to cooler waters, but through behavioural plasticity and social flexibility.

As the world’s oceans continue to heat up, understanding the outcomes of these novel species interactions, whether friend or foe, will be critical for predicting how reef communities will be reshaped in a rapidly warming ocean.

Read the paper

Read the full paper here: https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.70100