This blog post is provided by Oliver M. Poole and tells the #StoryBehindThePaper for the article “Long-range pollen transport across the North Sea: Insights from migratory hoverflies landing on a remote oil rig”, which was recently published in Journal of Animal Ecology. This study utilised samples from an oil rig operator to determine migratory movements of hoverflies and the pollen they transport across the North Sea and discusses long-distance pollination.

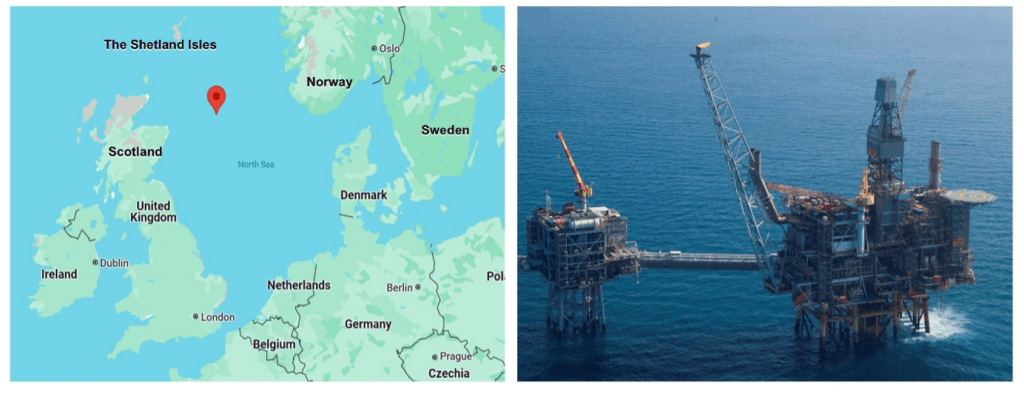

Found far out at sea and with little obvious use to animals, oil rigs are not often associated with any aspect of animal ecology, least of all benefiting terrestrial animals. However, a curious phenomenon discovered by an oil rig operator has revealed that these structures are in fact being used by a group of migratory animals, namely hoverflies, a family of flies known for their pollination services. In the UK there are currently five oil rigs in operation, all of which are situated in the North Sea and located many kilometres from landfall. While the isolation and harsh environment might seem an uncrossable barrier to most terrestrial animals, migrant hoverflies are often tasked with impressive feats of endurance and evidently are not swayed by the vastness of a North Sea crossing. When Craig Hannah, the operator who made the discovery contacted our research group, we set out to see what else there was to uncover from this unusual occurrence.

Hoverflies are a family of pollinating insects in the order Diptera, which hosts a multitude of species that engage in seasonal migration. The journeys these migratory species make, which are best characterised in western Europe, are enormous with thousands of kilometres travelled by flies that are smaller than the size of a one cent coin. Some of these journeys involve the challenge of traversing significant physical barriers including mountain ranges and large bodies of water, including oceans. Until recently it was unclear whether hoverflies could cross the North Sea during their migration. It became evident that this oil rig was acting as a beacon and was being utilised by insects making crossings of the North Sea. While we pondered what else there was to learn from this, Craig began collecting and sending over samples.

We were interested in the movement patterns of these migratory events and the pollen these hoverflies may carry across this large expanse of open sea. As the oil rig was situated approximately 200 km from the nearest point of land and unsurprisingly had no flowers growing on the rig itself, we knew that pollen found on and in the hoverflies would be from plants visited at locations where these individuals had departed. This information meant that we could confidently identify what plant species were being transported between otherwise genetically isolated populations. We sampled 121 marmalade hoverflies (Episyrphus balteatus) using DNA barcoding and revealed that 92% were carrying pollen with an average of eight plant species per individual. Among the most common plants were common nettle (Urtica dioica), black elder (Sambucus nigra), and meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria), but in total over 100 plant species were detected using our methods. Pollen from vegetable, legume, cereal, nut and fruit species were also identified. While this provides tantalising initial evidence that migratory hoverflies might be unique in their potential to facilitate the spread of beneficial alleles of food and crop pollen over large distances, the extent of this benefit in aiding the adaptation of plant populations in a changing planet remains to be investigated.

Hoverflies migrate south in autumn to avoid the deteriorating weather conditions and general resource depletion in northern latitudes, while in late spring they fly northwards to utilise uncongested breeding sites and spring growth. Since Craig had been sending us samples over multiple years and at different points of the year, we were able to characterise which pollen species were being moved in southward autumn and northward spring migration. We found that pollen transported during the northward migration events were more similar to each other in species composition when compared to the southward migration event. This told us that the hoverflies were utilising different plant species at different times of the year but that these differences were likely due to changes in plant availability rather than plant preference due to their broad diets.

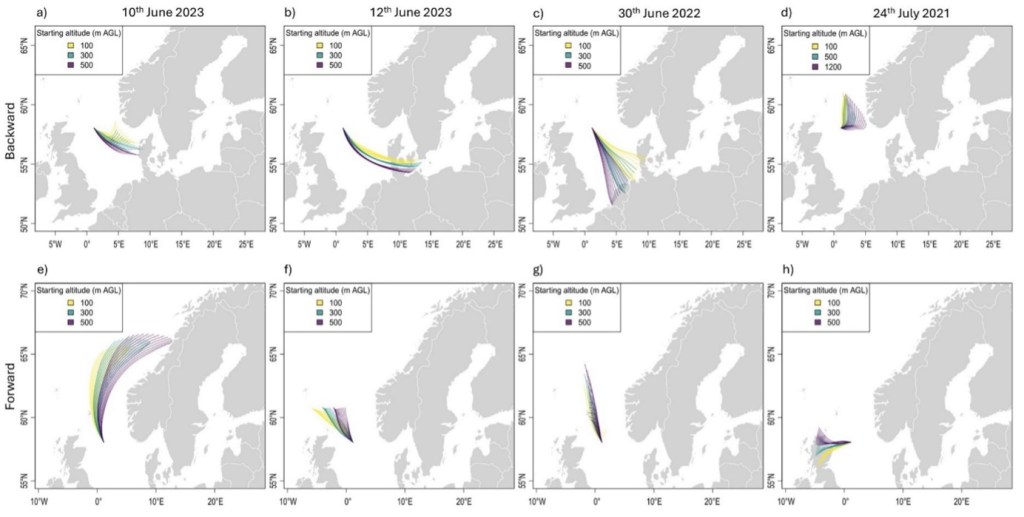

Utilising a weather model referred to as HYSPLIT (Hybrid Single-Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory) we were able to model the likely wind trajectories that these hoverflies took to arrive at the oil rig, and importantly the likely forward movements of these hoverflies when they left the oil rig. The HYSPLIT analysis revealed that origins of northward migration were from the Netherlands, northern Germany, and Denmark, all over 500 km away from the oil rig. Whereas, during southward migration, the results suggested that these hoverflies travelled from Norway. Forward trajectory analysis, determining where these hoverflies might end up after leaving the oil rig, suggested potential destinations including Norway or the Shetland Islands around 250 km away for the northward and Scotland for the southward migrations. Interestingly, in most cases Craig reported hoverflies appearing to stay on the oil rig for up to 12 hours, suggesting that they were using it as a pit stop on their 700+ km trip across the sea.

The importance of our findings put into perspective the magnitude of insect migratory journeys. In a paper published by Karl Wotton and collaborators, it was estimated that one to four billion day-flying hoverflies migrate in and out of southern Britain every year. While there are unlikely to be quite as many insects crossing the North Sea, the numbers provide a glimpse into the scale at which pollen is distributed via these means. These findings were only made possible from this unexpected collaboration, and we are thrilled to know that Craig and his colleagues working in area devoid of terrestrial life are still amazed by something as small as a hoverfly and have the curiosity to ask ‘why?’.

About the author:

I am a PhD student working on migratory hoverfly physiology down in Cornwall at the University of Exeter and am a co-author on this paper. I share a love for nature with most of those who also work in the field and spend far too much of my time trail running along the Cornish coast.

Read the paper:

https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1365-2656.70126

Please can I be credited for the blog I wrote. Thanks, Oliver Poole (Co-author on the paper).

Hi Oliver,

Apologies for the mix-up, the blog has now been updated to credit you. Thanks for catching that and for your patience!