This blog post is provided by Yu-Wen Yang and tells the #StoryBehindThePaper for the article “Relative brain size explains migratory/resident tendency in birds: Partial altitudinal migration in Asian house martins“, which was recently published in Journal of Animal Ecology. This study explores why some martins choose to stay while others migrate by comparing their morphological traits and breeding performance.

In the valleys of Lishan at Taiwan’s mountains, it’s common to see Asian house martins—a graceful swallow species—swirling high up in the sky. They are feeding on flying insects, including various fly and moth species. In spring, thousands of Asian house martins gather around human buildings in a Lishan village covered with orchards and forests, nesting under the roofs and raising their young. As weather turns colder, many leave the area but still some of them stay year-round.

The migratory choice of Asian house martins

What got my interest is why some martins choose to stay while others migrate? Clearly, both later-would-be migrants and residents face the same environmental conditions at the end of the breeding season, so what makes them behave differently? Past studies tried to explain this phenomenon with two perspectives. Some scientists believe that only those able to endure harsh winter conditions or outcompete conspecifics stay at the breeding ground. That is, residents need to have greater cold tolerance, higher fasting endurance, stronger dominance, or increased intelligence . Others argue that individuals that occupy high-quality nesting sites to increase fecundity have stronger motivation to stay on the breeding grounds. Therefore, we should see higher breeding success in residents. By comparing the morphological traits and breeding performance between migrants and residents, we expect to pinpoint the deterministic factor for their migratory behavior.

Under the generous consent of the owners of two buildings, we regularly banded house martins for several years. The huge colonies nesting in human buildings makes the banding surveys efficient, but it requires some tricks. Before sunrise, we snuck onto the balconies to set up mist-nets to surround the colonies, being extremely careful not to make any noise. Shortly after dawn, one or two individuals start leaving their nests, then the whole colony follows. As they hopped off and caught flight in mid-air, most of them would run into our nets. We then banded them with numbered aluminum rings and took body measurements. During the middle and late breeding season, we could catch up to 300 birds in each building on one single morning!

Innovativeness is the key for wintering in high mountains

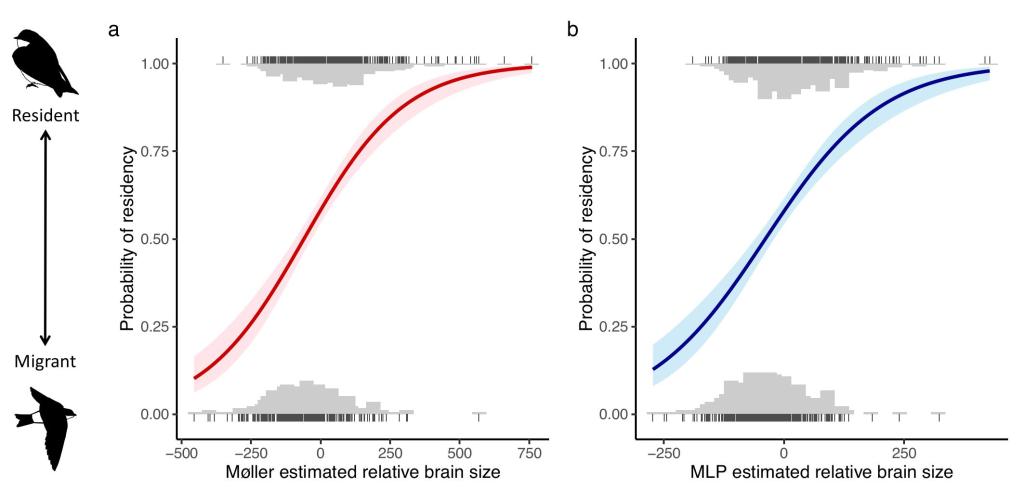

Based on these records, we grouped individuals into migrants and residents by whether they were present in our study site during the winter. We ran statistical models to estimate the probabilities of being a resident with the measured data, including body metrices, sex, breeding performance, and age. We were surprised to find that relative brain size (transformed from cranial size estimation) best predicted their migratory tactics! Residents generally had larger relative brain sizes than migrants.

“In birds, relative brain sizes are correlated with foraging innovativeness and behavioral flexibility, which may be beneficial for survival in harsh winter conditions.”

Larger brains indicate more innovativeness and behavioral flexibility, which may enable birds to utilize alternative food sources and roosting sites, or develop novel foraging approaches. In winter when temperatures drop and food sources decline, these abilities may help residents stay at high elevations. Meanwhile, migrants acquire a more mobile life style, prioritizing flight over innovativeness, and thus a smaller brain is more advantageous for them. The correlation between brain size and migratory propensity has been discovered in cross-species comparison studies, but hasn’t been tested within a single population before. Our study is the first one to confirm its effect between conspecifics.

Although we did not find any novel foraging approaches in Asian house martins, we observed unprecedented thermoregulation behaviors. For example, resident house martins continued to sleep in their nests during winter (the non-breeding season), alone or with their partners. We found that they delayed leaving their nests in the morning when temperature is really low. On one especially cold morning, we saw six house martins roosting in one single nest. Apparently, the resident house martins did not just skip migration and then chill out, but actively adjusted their behaviors to survive in the challenging winter.

The Asian house martins have taught us that innovativeness can help overcome environmental challenges, even in these small birds weighing less than one percent of us. Next time when you see swallows flying by, take a moment to watch their behaviors and imagine how brain size could have influenced their journeys.

Read the paper:

https://besjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1365-2656.70134