This blog post is provided by Aliénor Stahl, Marc Pépino, Andrea Bertolo and Pierre Magnan and tells the #StoryBehindThePaper for the article “Behavioural tactics across thermal gradients align with partial morphological divergence in brook charr”, which was recently published in the Journal of Animal Ecology. In their study, Stahl and colleagues reveal how the Brook charr uses thermal layers in its native lakes of Canada, providing new insight into the resilience of their populations to change.

This blog post is also available to read in French

Movement is one of the first conditions of life. It is how living beings explore, feed, hide, and find company. But while humans move across a flat surface, fish move through a true three-dimensional world. For them, “up” and “down” matter just as much as “left” and “right”. Their choices reach into entire layers of water that we never see; meaning that to understand a fish’s life, we need to know not just where it goes, but where in the water column it chooses to be. We need 3D clues to a 3D existence.

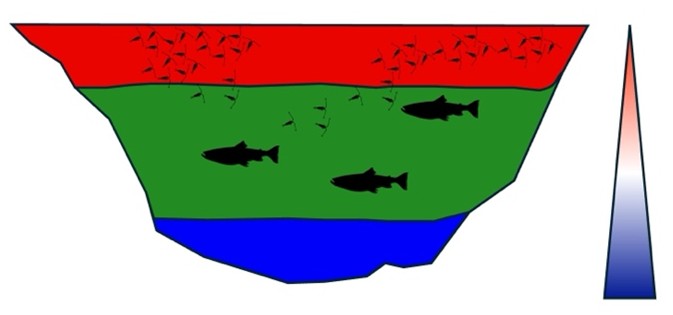

This curiosity has taken on new weight as climate change warms freshwater ecosystems. Lakes are shifting, and species that rely on cold water are the first to feel the pressure. If you’ve swum in a lake in summer, you’ve felt this structure yourself: warm water at the surface, then a sudden plunge into cold the moment you dive a bit deeper. Lakes become thermal sandwiches: warm water on top, cold water at the bottom, and a dividing layer between them.

For brook charr, a cold-water fish, each of these layers offers something different: For brook charr, a cold-water fish, each of these layers offers something different:

- The deep cold layer is safest for their bodies and sometimes hides unexpected feeding opportunities.

- The warm upper layer is rich with food but dangerously hot on summer days.

- The middle layer is comfortable but offers little to eat.

There is no single “best” choice. Just as we do not spend our whole lives in the kitchen, fish move between layers to meet their needs -warming up, cooling down, hunting, resting. Their world is a constant balancing act.

How do we follow animals that never stop moving?

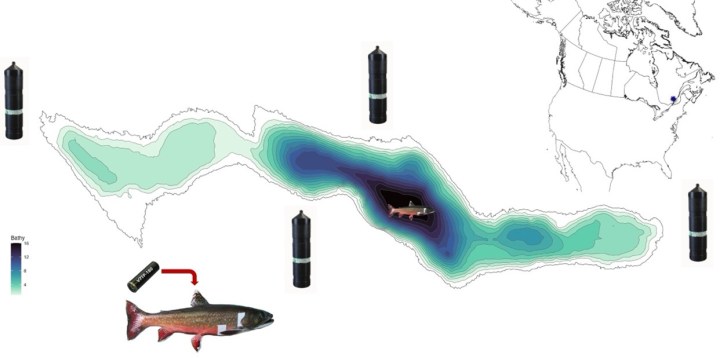

To watch the charr in action, we filled the lake with underwater listening stations (receivers that can “hear” tiny acoustic signals). Each fish carried a small tag that emitted its personal identification code every minute or so. By comparing which receivers picked up the signal and at what time, we could work out exactly where each fish was, down to the minute. For two whole summers, we watched charr draw invisible paths through the lake.

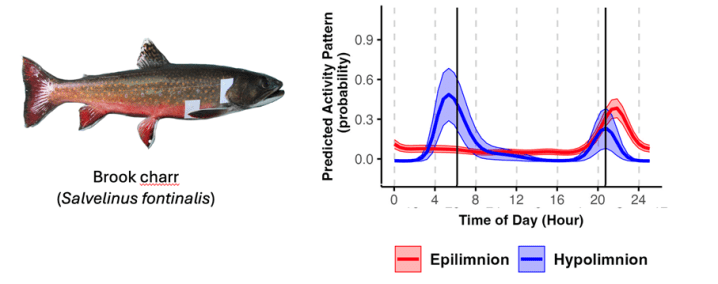

Once we had this 3D map of their movements, we looked at how often they used each layer and at what times of day. We expected them to move into the warm surface layer at dusk, when prey are active. What surprised us was how often they also ventured deep into the cold bottom layer -and, unexpectedly, at both dawn and dusk. These forays weren’t random spurts of exploration. They followed strong, consistent daily rhythms.

Even more striking was that individuals behaved in very different, but repeatable, ways. This revealed two clear tactics:

The “cool” tactic

Fish that spent more time in the cooler, deeper layers of the lake tended to have sleeker bodies. They were slimmer overall, with narrower heads and a thinner “tail stem” connecting the body to the tail. This streamlined shape helps reduce drag, making it easier to swim steadily over longer distances in open water.

The “warm” tactic

Fish that preferred the warmer, upper layers looked subtly different. Their bodies were deeper, their heads a bit broader, and their tail stems thicker. Rather than being built for long, efficient cruising, these fish seemed shaped for quick manoeuvres and short bursts of speed.

In other words, the fish weren’t simply wandering. Their movement patterns were linked to their physical form; behaviour and body evolving hand-in-hand. Brook charr in the same lake, facing the same conditions, effectively lived in different “worlds” and used them in different ways.

This hidden individuality matters. When environmental pressure increases (as it already is with warming lakes), populations with diverse tactics are more robust. They are less likely to collapse because they are not all relying on the same strategy.

Why does this matter for conservation?

Learning how fish use thermal layers helps us:

- anticipate how cold-water species will respond as lakes warm

- identify and protect cooling refuges

- understand that individuals, and not just species, hold the key to resilience

Climate change is reshaping freshwater habitats more quickly than many species can adapt. The layers charr use today may not exist in the same form tomorrow. Whether their finely tuned tactics will still serve them in a warmer world is uncertain.

But by revealing the secret journeys they make, minute by minute, layer by layer, we gain insight into how these fish solve problems, navigate risk, and carve out their own paths. They are not passive victims of their environment. They are decision-makers, explorers, and survivors.

And in watching the quiet complexity of their movements, we come a little closer to understanding the hidden worlds beneath the surface -and what we stand to lose if we fail to protect them.

Read the paper

Read the full paper here: https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.70195