This blog post is provided by Catherine Sheard and tells the #StoryBehindThePaper for the paper “Anthropogenic nest material use in a global sample of birds”, which was recently published in the Journal of Animal Ecology. This study investigates patterns in the use of artificial materials in bird nests.

I had been collecting data on bird nests for a number of years, including thinking about how bird bill morphology relates to nest material use. This meant that I was reading a lot – a lot – of lists of materials that have been found in various bird nests. Occasionally, these lists would be decidedly unnatural, such as string, cellophane, or a doll’s head. I began to wonder if there was some pattern here, if it was known what sorts of birds did and did not use artificial nest materials.

In 1933, Ernest Warren wrote a letter to Nature, noting that a local pied crow (Corvus scapulatus, now Corvus albus) had placed pieces of wire in its nest. Over 90 years later, dozens upon dozens of papers are ringing alarm bells about the amount of anthropogenic materials in nests around the world, given that artificial materials can be inadvertently ingested, wrapped around chicks’ necks, and/or cause genotoxic damage. Evidence from population-level studies, as well as from a recent study of this phenomenon in 125 species, point to many possible correlates of variation in this behaviour, but it was unclear how many of these would apply across many different taxonomic groups and ecological contexts.

The first challenge was collecting the data. Lucy Stott, the second author of the final published study and then a first-year undergraduate, read thousands of lists of nest materials to determine which species have been recorded as using anthropogenic materials. She also separately scored these lists for the presence of plastic material, given their increased danger to birds (e.g., ingestion, strangulation) and their inability to biodegrade. Of the bird species we could get data on, 4.7% of species were known to incorporate anthropogenic materials into their nests, and 1.5% plastic materials specifically; we suspect that this is an underestimate!

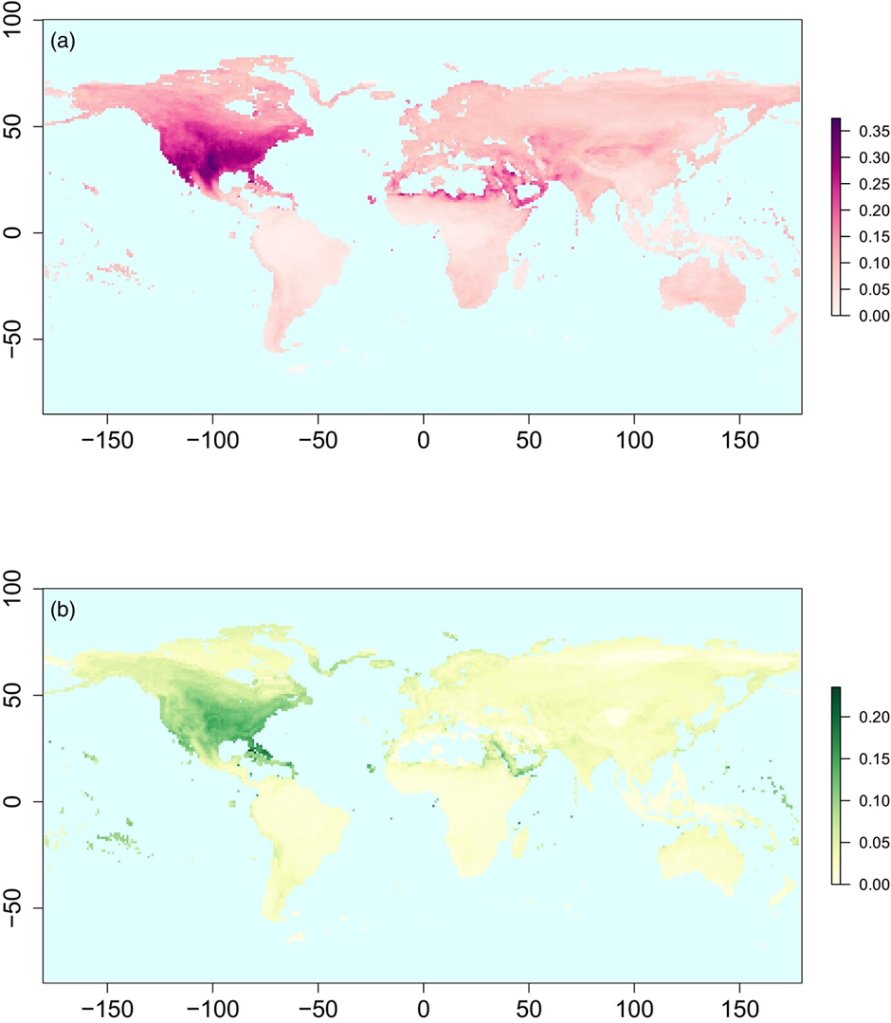

From there, we ran Bayesian phylogenetic mixed models to evaluate potential relationships between known anthropogenic/plastic nest material use and our various hypothesized correlates. We found that species were more likely to have been recorded as incorporating anthropogenic material if they were well-studied, lived in close proximity to human landscape modification (e.g., in cities or farmland), had been recorded as building their nest in artificial locations (e.g., on telephone poles or the roofs of houses, a proxy for human tolerance), or generally were known to be able to incorporate a large number of different types of materials into their nests. We also found statistically significant variation in anthropogenic nest material use between birds living in different biomes – for example, birds living in deserts were more likely to use anthropogenic nest materials than birds living in tropical rainforests, even after controlling for research effort (how well-studied the species are) and proximity to humans. We interpreted this as birds responding to the availability of natural nest materials, which are likely more abundant in rainforests than in deserts, though further research would be needed to determine the exact behavioural cause underlying this pattern.

Some animal species are able to persist in human-modified landscapes; others decline rapidly. Part of this variation between species in human tolerance relates to differences in behaviour, likely including how birds construct their nests. Understanding what types of animals do and do not exhibit these human-associated behaviours can help us to better predict future responses to further landscape modifications. Such studies also tell us something interesting about the evolution of animal behaviour more broadly – who can change their behaviours quickly, and why might that be?

About the author

Catherine Sheard is an Interdisciplinary Fellow at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. Her research uses phylogenetic comparative methods to study variation in traits between species across broad swaths of space and time. Website: https://catherinesheard.weebly.com/

Read the paper

Read the full paper here: Sheard, C., Stott, L., Street, S. E., Healy, S. D., Sugasawa, S., & Lala, K. N. (2024). Anthropogenic nest material use in a global sample of birds. Journal of Animal Ecology, 00, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.14078