This blog post is provided by Rachakonda Sreekar and Eben Goodale and tells their #StoryBehindthePaper for the article ‘Endemicity and land‐use type influence the abundance–range‐size relationship of birds on a tropical island’, which was recently published in Journal of Animal Ecology.

Have you heard of a species going extinct? More often than not, it was an island endemic, like the Dodo, the Thylacine, and the recently extinct Bramble Cay Melomys. The positive abundance–range size relationship is an ecological rule that may explain the vulnerability of island endemics. According to this rule, species that have small range sizes will also have low abundances – a double threat. First threat: small ranged species are highly vulnerable to both natural and human-made disturbances. Second threat: less abundant species are vulnerable to random fluctuations in population size.

We tried to understand how island endemics survive this double threat on the tropical island of Sri Lanka. Though separated from India by only ~65 km, Sri Lanka has many endemics in its southwest. The central mountain massif makes rainfall much higher in this ‘wet zone’; the northern part of the country is arid and difficult for rainforest animals to cross. But the southwestern part of the country is also the area with the largest human population, and now pockets of forest remain only as fragments in a sea of agriculture.

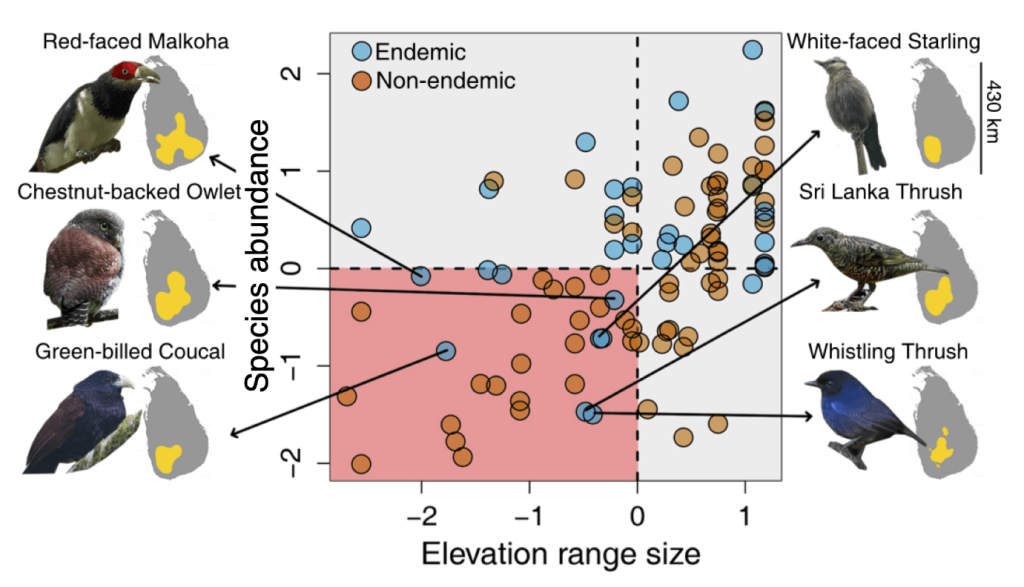

We studied the relationship between bird species’ abundance and their elevational range size. Specifically, we asked whether this relationship differs between endemic and non-endemic species, or whether it varies between three different land-use types – from naturally occurring rainforests, to semi-natural plantations, to intensive agriculture.

We found a positive abundance-range relationship, but one that depended on endemicity and land-use type. For any particular range size, endemics tend to be more abundant than non-endemics. This pattern was seen in rainforests and semi-natural plantations but not in agriculture, where endemics and non-endemics were similarly abundant. We interpret our results as demonstrating that lower species richness on islands may lead to higher abundances (a classic hypothesis formulated by Robert MacArthur back in 1972), and island endemics may be particularly well adapted to the island’s conditions. However, this adaptation is disrupted by human disturbance.

We found that smaller ranged endemic species have higher abundances in comparison to non-endemics, resulting in a comparatively shallow sloped abundance-range size relationship for endemics. Increasing abundances reduces the chances of extirpation due to random fluctuation in population sizes. MacArthur and colleagues already suggested the idea in 1972 that lower species richness on islands may facilitate higher abundances. This may be because island species are evolved to adapt to island environments.

In contrast, we found that agriculture seriously affects the abundances of small-ranged endemic species, resulting in a comparatively steeper sloped abundance-range size relationship for endemics. In conclusion, a stronger adaptation to specific island environments is advantageous in natural environments, but a drawback in human-modified environments.

We then used the abundance-range size relationship to identify Sri Lankan endemic species that have both small abundances and range sizes, and have high specificity to rainforests, with the top four species being Sri Lanka Whistling Thrush, Red-faced Malkoha, Sri Lanka Scaly Thrush, and White-faced Starling. We conclude that abundance-range size relationships can help identify species most at risk of extinction, and suggest how protected areas should be planned to conserve them.