This blog post is provided by Madan K. Oli, George D. Smith, Michael J. McGrady, Vratika Chaudhary, Chris J. Rollie, Richard Mearns, Ian Newton and Xavier Lambin and tells the #StoryBehindthePaper for the paper “Reproductive Performance of Peregrine Falcons Relative to the Use of Organochlorine Pesticides, 1946-2021”, which was recently published in Journal of Animal Ecology. They explore how banning pesticides like DDT impacted Peregrine Falcons by increasing breeding success and reducing mortality that these chemicals caused.

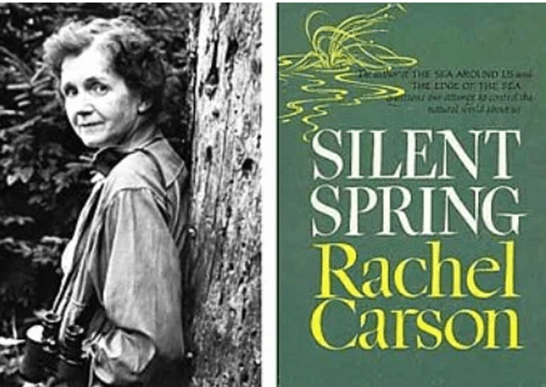

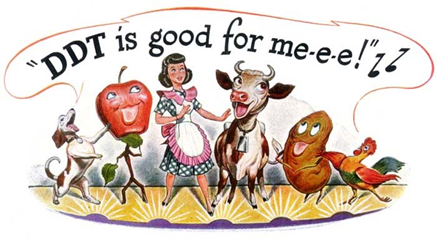

More than 60 years have elapsed since the publication of the well-known environmental classic ‘Silent Spring’. This remarkable book, written by writer-naturalist Rachel Carson (1962), highlighted the devastating impacts that modern organochlorine pesticides were having on wildlife world-wide. These synthetic chemicals included such well-known products as DDT and the much more toxic cyclodiene compounds, such as aldrin and dieldrin. These different compounds affected birds in different ways, with DDT reducing reproductive rates by causing eggshell thinning, and the cyclodienes through direct mortality. Organochlorines were also highly soluble in the body fat of animals and extremely persistent in the environment. This combination of features meant that birds-of-prey were often exposed to relatively high concentrations, because they gained a cumulative dose from all the prey they ate. Pulling together the scientific results in the way it did, Silent Spring firmly dispensed with the fashionable notion that modern pesticides could raise crop production with no significant environmental downsides. For many, Silent Spring marked the beginning of the modern environmental movement.

Effects of organochlorine pesticides on wildlife became apparent soon after they came into widespread agricultural use, around the mid-20th century. One of the most affected species was the bird-eating Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus) which, along with some other raptors, suddenly showed catastrophic population declines through much of its global range (Ratcliffe 1970, 1993; Newton 1979, 1986). The declines seemed due to a combination of poor reproduction (owing mainly to DDT) and to enhanced mortality (due mainly to aldrin and dieldrin). The relative importance of these two impacts varied regionally, depending on local patterns of pesticide use. The Peregrine Falcon, by dint of its charisma and near-global distribution, became a cause célèbre in the fight against these chemicals. It also became the most extensively studied raptor in the world.

The establishment over the ensuing years of a causal link between organochlorine use and declines in Peregrines and other wildlife eventually led to the progressive reduction and eventual banning of organochlorine use in the UK and many other countries (Cade et al. 1988). Once these chemicals had gone from use, populations of affected bird species began to recover, albeit at varying rates (Wyllie & Newton 1991; Newton & Wyllie 1992; Newton 1998; Banks et al. 2010).

In their current paper, the authors – comprising a mix of professional and citizen scientists – combine 75-yrs (1946 – 2021) of Peregrine monitoring data from southern Scotland to show that: (1) Peregrine breeding success increased steadily over several decades following the reduction and eventual banning of organochlorine pesticide use; (2) improvements in breeding performance were accompanied by increases in breeding numbers; and (3) these changes were somewhat later and more marked in the most arable parts of the region where pesticide use is likely to have been greatest. Over and above any pesticide impacts, the study also showed that the main natural variable affecting annual breeding success was the weather: excessive cold and rain in May, around the time the eggs hatched, tended to reduce the production of young. One problem remains, however, namely that of persecution on grouse moors. Only when this killing and nest destruction can be stopped is the species likely to breed again over the whole of its potential range in Britain.

Overall, these results were consistent with the hypothesis that reproductive failure caused by organochlorine pesticides was an important driver of the decline in the south Scottish Peregrine population, and that improvements in breeding performance following reduction in the use of these chemicals facilitated the observed recovery in the population. Three main take-home messages emerge: first, the great contribution that can be made by unpaid citizen scientists to conservation research; secondly, the value of predatory birds as environmental monitors; and thirdly, the value of long-term population studies in assessing the impacts of environmental variables, whether natural or man-made.

Literature cited

Banks, A.N., Crick, H.Q.P., Coombes, R., Benn, S., Ratcliffe, D.A. & Humphreys, E.M. 2010. The breeding status of Peregrine Falcons Falco peregrinus in the UK and Isle of Man in 2002. Bird Study, 57, 421-436.

Cade, T.J., Enderson, J.H., Thelander, C.G. & White, C.M. 1988. Peregrine Falcon Populations – Their management and recovery. The Peregrine Fund, Boise.

Carson, R. 1962. Silent Spring. Houghton Mifflin, New York

Newton, I. 1979. Population Ecology of Raptors. T. and A.D. Poyser, Birkhamsted, U. K.

Newton, I. 1986. The Sparrowhawk. T. and A.D. Poyser, Calton, U. K.

Newton, I., 1998. Population Limitation in Birds. Academic press London

Newton, I. & Wyllie, I. (1992) Recovery of a sparrowhawk population in relation to declining pesticide contamination. Journal of Applied Ecology, 29, 476-484.

Ratcliffe, D.A. 1970. Changes attributable to pesticides in egg breakage frequency and eggshell thickness in some British birds. Journal of Applied Ecology, 7, 67-115.

Ratcliffe, D.A. 1993. The Peregrine Falcon, Second edn. T. & A. D. Poyser, Berkhamsted, U.K.

Wyllie, I. and Newton, I., 1991. Demography of an increasing population of Sparrowhawks. Journal of Animal Ecology 60: 749-766.

Read the paper

Read the full paper here: Oli, M. K., Smith, G. D., McGrady, M. J., Chaudhary, V., Rollie, C. J., Mearns, R., Newton, I., & Lambin, X. (2023). Reproductive performance of Peregrine falcons relative to the use of organochlorine pesticides, 1946–2021. Journal of Animal Ecology, 00, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.14006