This blog post is provided by Dalmiro Borzone Mas and Pablo Scarabotti and tells the #StoryBehindthePaper for the paper “Symmetries and asymmetries in the topological roles of piscivorous fishes between occurrence networks and food webs“, which was recently published in the Journal of Animal Ecology. In their study, they explore whether occurrence networks and food webs of the Paraná River have a modular structure and which traits are related to the modular connection capacity of the species in each type of network. They find that occurrence networks and food webs of the Paraná River floodplain are indeed modular and that large predatory species have a role as food web connectors, whereas small species have a role as connectors in occurrence networks.

This post is also available in Spanish.

Ecosystems are complex entities where species interact with each other and with their environment, creating ecological networks. The representation of a system as a network can be useful to understand how the components are related to each other, and the ways in which they interact. Depending on the ecological network we are studying, the components (called nodes and links) can be different entities. In a food web, nodes represent preys and predators, and links indicate trophic interactions (who eats whom). It is also possible to build networks to analyze the relationships between species and the habitats they use. In these networks, called occurrence networks, species and sites are the nodes while the links indicate the habitats used by each species. In ecological networks, species can aggregate in blocks that interact more frequently with each other than with the remaining species. These blocks are called modules, and their presence is a prominent feature in many kinds of networks such as spatial networks, plant-pollinator interactions and food webs. However, network modules are not completely isolated, since there are species that have many interactions with other modules. These species are called modular connectors, and they play a central role in the cohesion, dynamics, and stability of networks.

In a study recently published in the Journal of Animal Ecology, we analyzed the way in which piscivorous fish in the Paraná River and its floodplain act as connectors in occurrence networks and food webs. Our main hypotheses were that (a) predatory fish are important connectors of the compartments of food webs and occurrence networks and (b) that body size is a key trait driving this function. We analyzed which body traits were related to the connection capacity of each species and whether these traits have the same effect on occurrence networks and food webs. Our research questions were: Do the occurrence networks and food webs of the Paraná River have a modular structure? And, which traits are related to the modular connection capacity of the species in each type of network?

Body size is a key trait in ecology; it determines the metabolic rate, the diversity of prey ingested, and the tolerance to adverse environmental conditions, among other properties. In turn, the ecomorphology of each species (for example, the shape of the body and the type of teeth) can provide information on swimming ability and prey capture strategy. In this sense, both body size and ecomorphology can determine the interactions that each species has and its role as a connector in the network. However, the effect of each trait on a species’ role as modular connectors may not be the same in occurrence networks and food webs. For example, larger predators have greater diversity of prey, but this is offset by having greater environmental requirements to remain in a particular habitat. In this sense, body size can have a positive effect on the ability of the species to connect the food web compartments (allowing the capture of a broader spectrum of prey) and a negative effect on the ability to connect occurrence networks (prohibiting permanence in sites with harsh environmental conditions).

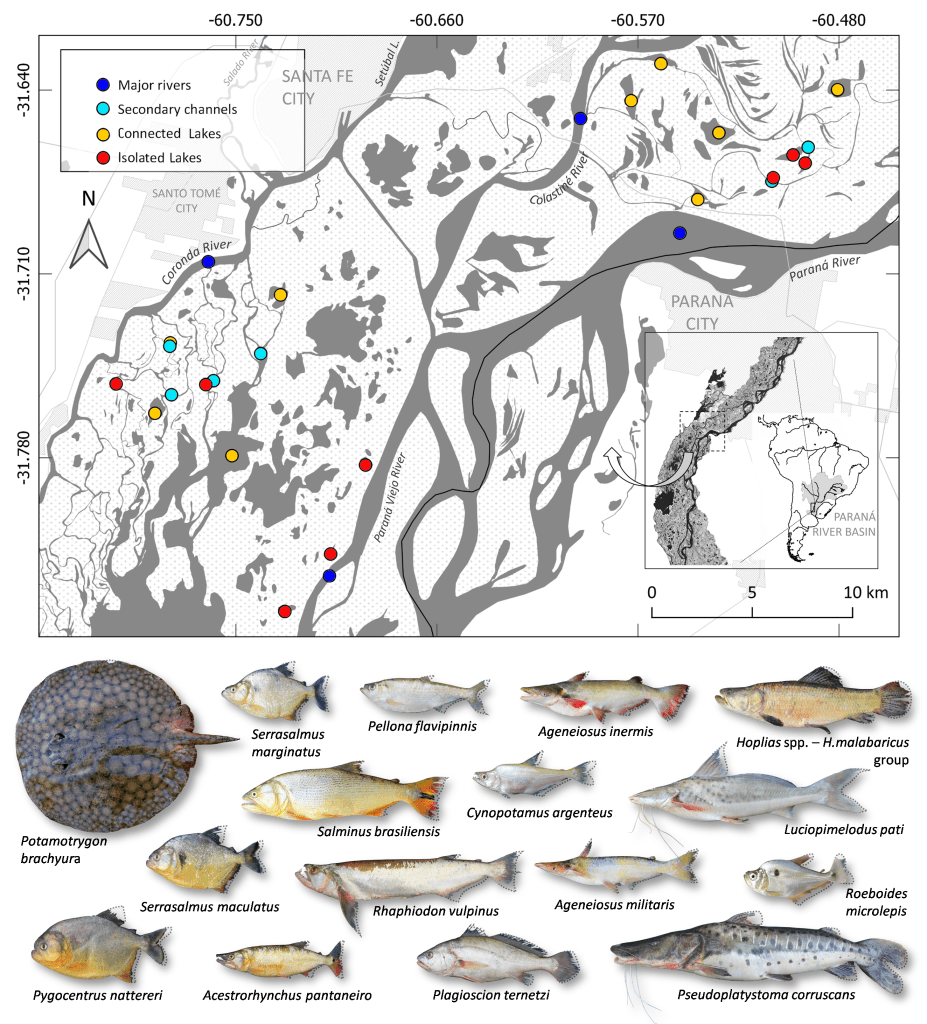

To answer our questions, we performed field surveys, where we recorded the types of habitats and the prey consumed by each of sixteen predatory fish species. The Paraná River and its floodplain conform a complex ecosystem with a great diversity of habitats. These habitats range from channels of more than a kilometer wide and 20 meters deep, small streams meandering between the islands of the floodplain, to lakes located within the islands that can be connected or isolated depending on the river level. In addition, the river exhibits significant seasonal variations in temperature and flow. The height of the river can vary between 3 to 4 meters in the same year, producing a deep change in the structure of the habitat and the isolation of the communities. In our study, we included 16 of the most important predatory fishes, including commercially important species such as the spotted surubí (P. corruscans), the dorado (S. brasiliensis), the giant river stingray (P. brachyura) and three species of piranhas (two species of Serrasalmus and Pygocentrus nattereri). In the sampling design, we considered the seasonal variation in temperature and river level, defining four environmental situations: Warm season with low or high river level and cold season with low or high river level. One hundred and fifty two communities were surveyed with 3048 individuals and 1277 trophic interactions recorded. For each species, we recorded the mean weight and 30 ecomorphological traits describing the body shape and coloration. Subsequently, we calculated the modularity of the networks in each environmental situation, the intermodular connection value of each predator (c-value) and the relationship between the c-value and the traits (body size and ecomorphology).

Our results showed that the occurrence networks and food webs of the Paraná River floodplain are systematically modular. In turn, we observed that the large predatory species have a role as food web connectors, whereas small species have a role as connectors in occurrence networks. These different effects of body size reflect the underlying mechanisms that drive the interactions in each network; where a large body size offers the possibility of capturing a greater variety of prey, but makes survival difficult in sites with harsh environmental conditions. In addition, we observed that the ecomorphological traits related to the connection of the modules change in different environmental situations. This work demonstrated that the networks of the Paraná River are modular and that certain species have key roles connecting the network modules. In turn, the asymmetric effect of body size tells us that we should be cautious about inferring roles in an ecological network based on other types of networks. Finally, this modular structure is sustained through time by species with dynamic roles, reflecting changes in the relationship between their traits and their ability to connect in each situation.

Read the paper

Borzone Mas, D., Scarabotti, P., Alvarenga, P., & Arim, M. (2022). Symmetries and asymmetries in the topological roles of piscivorous fishes between occurrence networks and food webs. Journal of Animal Ecology, 00, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13784